The roots of the mātṛkā-s in the śruti and the Kaumāra tradition

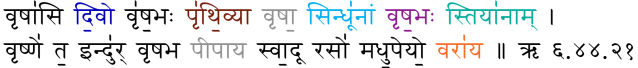

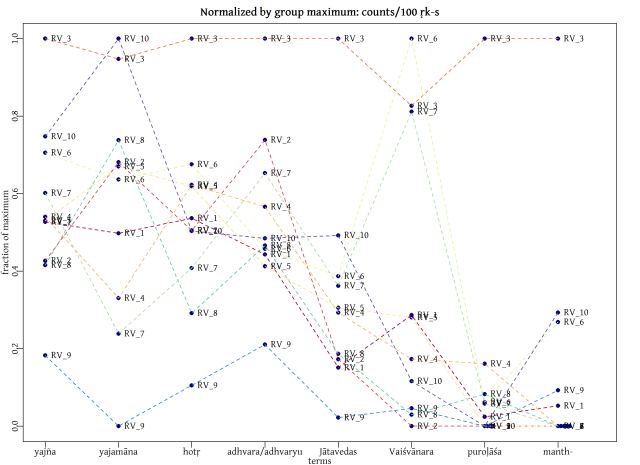

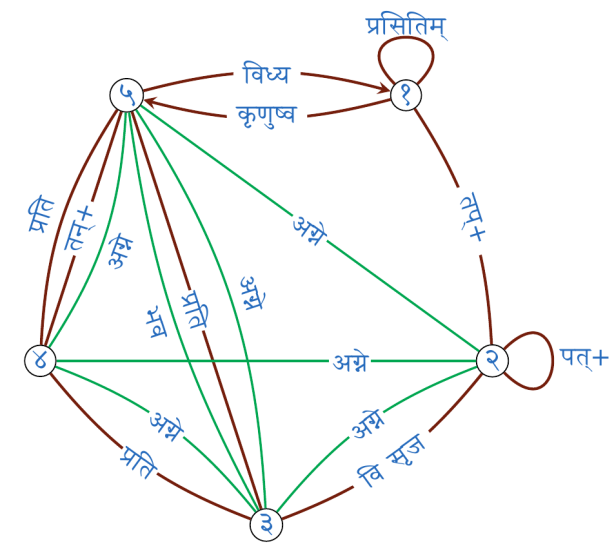

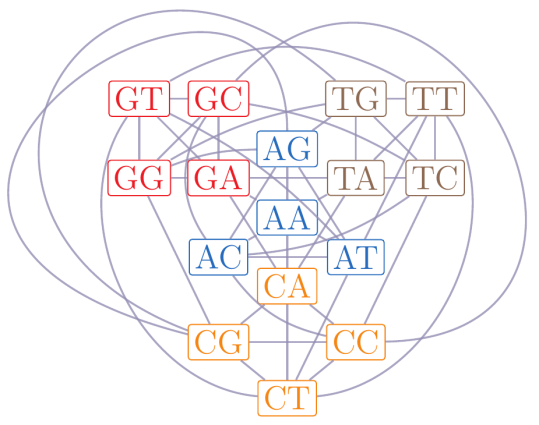

The standard list of 7/8 goddesses known as the mātṛkā-s is a hallmark feature of the classical religion: Brāhmī, Māheśvarī, Kaumārī, Vaiṣṇavī, Vārāhī, Indrāṇī, Cāmuṇḍā, sometimes with the central Caṇḍikā (Mahālakṣmī), to make a list of 8. Most of them are the female counterparts of the prominent gods of the classical pantheon. These goddesses have a relatively constant iconography throughout the Indosphere, starting from the Gupta age. Despite this relatively late arrival on the iconographic landscape, they have deep roots going back to the ancestral Indo-European religion and its earliest Indo-Aryan manifestation. Right in the Ṛgveda, we have the incantations for the Patnī-saṃyāja or the worship of the goddesses at the Gārhapatya altar (e.g., RV 2.32.4-8; RV 5.46.7-8), along with Agni Gṛhapati. Similar ṛk-s are also seen in the Atharvavedic tradition. Three types of goddesses can be discerned in these incantations: 1) The great trans-functional goddess of proto-Indo-European provenance, Sarasvatī; 2) The deva-patnī-s or the wives/female counterparts of the gods; 3) The “lunar goddesses”, Kuhū (Guṅgū), Sinīvālī, Rākā, Anumatī. Below we provide an Atharvavedic version of these incantations (the subset which is found in RV is effectively the equivalently).

yā rākā yā sinīvālī yā guṅgūr yā sarasvatī ।

indrāṇīm ahva ūtaye varuṇānīṃ svastaye ॥

I call she who is, Sinīvālī, who is Guṅgū, who is Rākā, who is Sarasvatī, for my aid I call Indrāṇī, and Varuṇāṇī for my well-being.

sinīvālīm anumatīṃ rākāṃ guṅgūṃ sarasvatīm ।

devānāṃ patnīr yā devī indrāṇīm avase huve ॥

I invoke for protection Sinīvālī, Anumatī, Rākā, Guṅgū, and Sarasvatī, the wives of the gods, and she who is the goddess Indrāṇī.

senāsi pṛthivī dhanaṃjayā aditir viśvarūpā sūryatvak ।

indrāṇī prāṣāṭ saṃjayantī tasyai ta enā haviṣā vidhema ॥

You are Senā (the goddess of the divine army), the Earth, the conqueress of wealth, Aditi, multiformed, and sun-skinned. O Indrāṇī, [for you] the prāṣāṭ call, O all-conquering one; we pay homage to her with this offering.

uta gnā vyantu devapatnīr indrāṇya1 gnāyy aśvinī rāṭ ।

ā rodasī varuṇānī śṛṇotu vyantu devīr ya ṛtur janīnām ॥

May the goddesses, the wives of the gods, come, Indrāṇī, Aśvinī, Agnāyi, and the Queen. May Rodasī [wife of the Marut-s] and Varuṇāṇī hear us, and the goddesses come to the ritual of the mothers.

yā viśpatnīndram asi pratīcī sahasra-stukābhiyantī devī ।

viṣṇoḥ patni tubhyaṃ rātā havīṃṣi patiṃ devi rādhase codayasva ॥

The Queen of the folks, you are Indra’s equal, the goddess with a thousand tresses, coming to us. O wife of Viṣṇu, to you, these offerings [are] made. O goddess, urge your husband to be liberal [towards us].

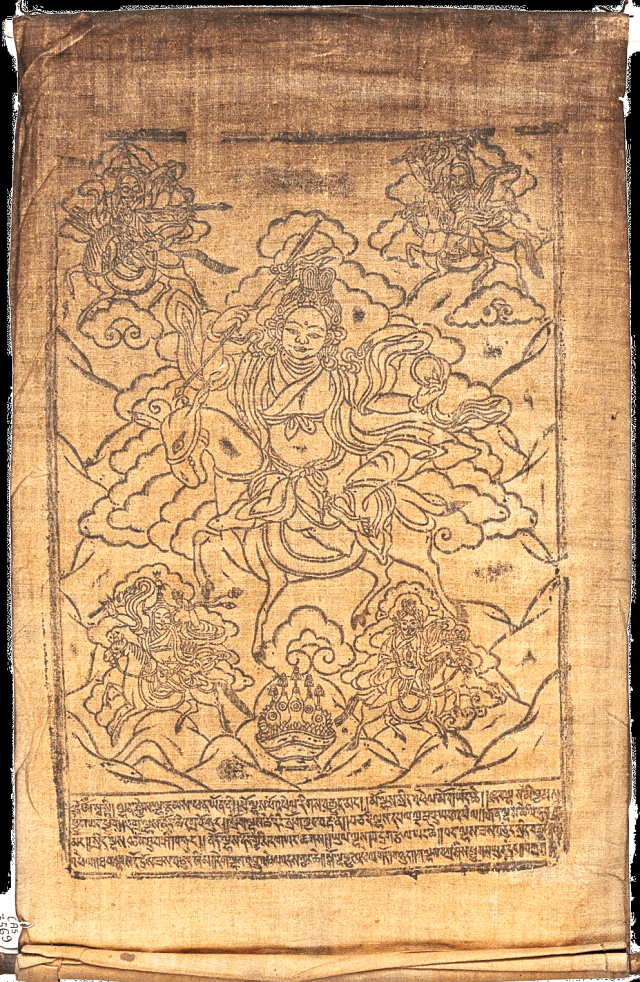

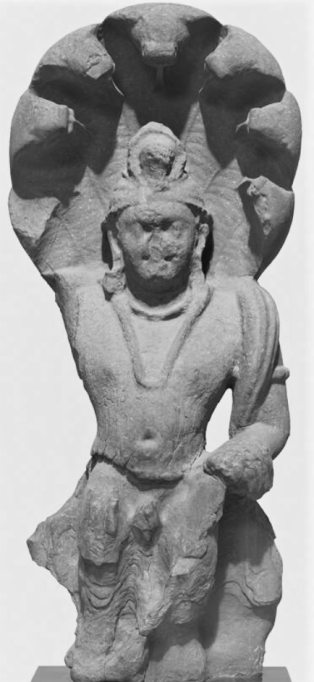

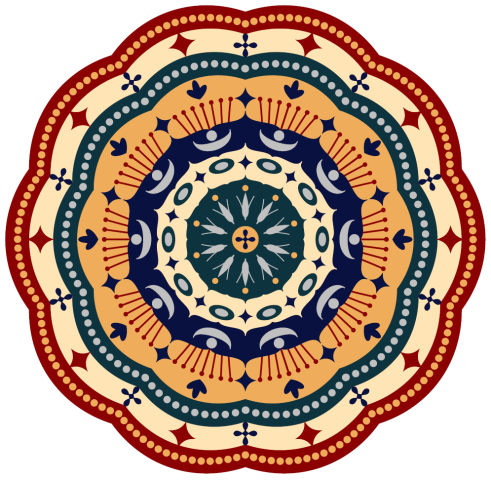

A five-headed Indrāṇī from a Nepalian mātṛkā-pūjā manuscript

Of these goddesses, Indrāṇī and Viṣṇupatnī (Vaiṣṇavī) are featured in most classic mātṛkā lists of the later religion. Another goddess from the classical mātṛkā list, Rudrāṇī, is seen in yajuṣ incantations of the Taittirīya and Kaṭha schools of the Kṛṣṇa-yajurveda. The goddess Senā is associated with the divine army. In the Kṛṣṇa-Yajurvedic Kaṭha and Maitrāyaṇi schools, Senā identified with Indrāṇī: indrāṇyai caruṃ nirvapet senāyām uttiṣṭhantyām । sénā vā indrāṇī । This association continues in the late Yajurvedic incantation known as the Āyuṣya-sūkta (Bodhāyana-mantra-praśna), where the same goddess is explicitly termed Indrasenā. In later tradition, she is seen as the wife of Skanda (Devasenā), who is also mentioned in the Āyuṣya-sūkta by her other name Ṣaṣṭhī.

A persistent pattern in these Vedic rituals is the presence of a single male god accompanying a cluster of goddesses. As noted above, Agni Gṛhapati is the single male deity who accompanies the goddesses receiving offerings in the Patnī-saṃyāja. The RV also repeatedly states that the wives of the gods arrive at the ritual accompanied by the god Tvaṣṭṛ (RV 1.22.9; 1.161.4; 2.31.4; 2.36.3; 6.50.13; 7.34.20; 7.34.22; 7.35.6; 10.18.6; 10.64.10; 10.66.3) Additionally, in the Taittirīya school we have two versions of the Devikā oblations. In the first of them, the god Tvaṣṭṛ accompanies the goddesses Sarasvatī and Sinīvālī. In the second, the god Dhātṛ (a later ectype of Tvaṣṭṛ [Footnote 1]) is invoked together with the goddesses Aditi, Anumatī, Rākā, Sinīvālī and Guṅgū. This pattern may be seen as analogous to the usual situation, wherein several male gods associated with different functions are spanned by a single transfunctional goddess — Sarasvatī [Footnote 2]. Here, a single male generative deity is associated with a multi-functional cluster of goddesses who actualize the dormant generative capacity of the former. While the Patnī-saṃyāja associated with the Śulagava ritual of the Śukla-yajurveda invokes the goddesses with Agni Gṛhapati as usual, it presents a unique set of them (Pāraskara-Gṛhya-Sūtra 3.8):

śūlagavaḥ ।

The impaled bull [sacrifice]

svargyaḥ paśavyaḥ putryo dhanyo yaśasya āyuṣyaḥ ।

It procures heaven, cattle, sons, riches, renown, long life.

aupāsanam araṇyaṃ hṛtvā vitānaṃ sādhayitvā raudraṃ paśum ālabheta ।

Having taken the aupāsana fire to the forest, and having performed the spreading [of grass], he should obtain the animal for Rudra.

sāṇḍam ।

With testicles (i.e., not castrated)

gaur vā śabdāt ।

Or a cow as the name [of the ritual specifies]

vapāṃ śrapayitvā sthālīpākam avadānāni ca rudrāya vapām antarikṣāya vasāṃ sthālīpāka-miśrānyavadānāni juhoty agnaye rudrāya śarvāya paśupataye ugrāyāśanaye bhavāya mahādevāyeśānāyeti ca ।

Having cooked the omentum, a plate of rice, and the cuts from [the victim], he offers the omentum to Rudra, the fat to the atmosphere, and the cuts of meat with the rice to Agni, Rudra, Śarva, Paśupati, Ugra, Aśani, Bhava, Mahādeva and Īśāna.

vanaspatiḥ ।

The Vanaspati (offering to the sacrificial post is made).

sviṣṭakṛd ante ।

At the end [offerings are made to Agni] Sviṣṭakṛt.

dig vyāghāraṇam ।

Then the sprinkling to the directions [is performed].

vyāghāraṇānte patnīḥ saṃyājayantīndrāṇyai rudrāṇyai śarvāṇyai bhavānyā agniṃ gṛhapatim iti ।

At the end of the sprinkling the offer the Patnī-saṃyāja oblations to Indrāṇī, Rudrāṇī, Śarvāṇi, Bhavānī, and Agni Gṛhapati.

lohitaṃ pālāśeṣu kūrceṣu rudrāya senābhyo baliṃ harati yās te rudra purastāt senās tābhya eṣa balis tābhyas te namo yās te rudra dakṣiṇataḥ senās tābhya eṣa balis tābhyas te namo yāste rudra paścāt senās tābhya eṣa balis tābhyas te namo yās te rudrottarataḥ senās tābhya eṣa balis tābhyas te namo yās te rudropariṣṭāt senās tābhya eṣa balis tābhyas te namo yās te rudrādhastāt senās tābhya eṣa balis tābhyas te nama iti ।

He [then] offers the blood [of the sacrificed bull] as bali with a bunch of Butea frondosa leaves to Rudra and his troops with [the incantations]: “O Rudra, those armies, which you have to the East (to the South; to the West; to the North; upwards; downwards), to them is this bali. Obeisance be to them and to you.”

ūvadhyaṃ lohita-liptam agnau prāsyaty adho vā nikhanati ।

He casts the gut and the blood-smeared remains into the fire or buries them beneath.

anuvātaṃ paśum avasthāpya rudrair upatiṣṭhate prathamottamābhyāṃ vā .anuvākābhyām ।

Having [placed the remains of] the animal such that the wind blows from himself to it, he goes towards it by [reciting] the Rudra incantations, or the first and last anuvāka [i.e., Śatarudrīya].

naitasya paśor grāmaṃ haranti ।

They do not take anything of the animal to the village.

etenaiva goyajño vyākhyātaḥ ।

By this the cow-sacrifice is also expounded.

pāyasenānartha-luptaḥ ।

It is done with an offering of milk, and the [rituals] not meant for it are omitted.

tasya tulyavayā gaur dakṣiṇā ।

A cow of the same age (as the sacrificed animal) is the ritual fee.}

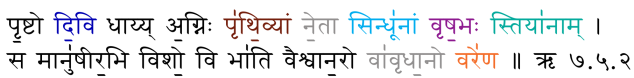

Thus, the Patnī-saṃyāja of the Śulagava departs from the classical one in combining Indrāṇī with the three raudra goddesses, Rudrāṇī, Śarvāṇi and Bhavānī. Hence, we are already seeing a hint of the tendencies in the mātṛkā system of the classical religion, wherein the māṭṛkā-s typically have an explicitly raudra connection. Indeed, this triad of raudra goddess might indicate a connection to the old name of Rudra, Tryambaka, which implies his association with three mothers. Other than the above-mentioned male deities coming with a cluster of goddesses, in the late Taittirīya tradition of the Bodhāyana-mantrapraśna, we see Skanda appearing with a cluster of 12 māṭṛkā-s:

aghorāya mahāghorāya nejameṣāya namo namaḥ ॥

āveśinī hy aśrumukhī kutuhalī hastinī jṛṃbhiṇī stambhinī mohinī ca ।

kṛṣṇā viśākhā vimalā brahmarātrī bhrātṛvyasaṃgheṣu-patanty amoghās tābhyo vai mātṛbhyo namo namaḥ ॥

Similarly, another late Taittirīya tradition, the Vaikhānasa-mantrapraśna, provides an incantation for a set of goddesses who are said to be born of Guha (i.e., Skanda) and said to bear the gaṇa of Rudra:

jvālā mālā gumbhinī guha-jātā raudraṃ gaṇaṃ yā bibhṛyāt surūpī svāhā ॥ VP 6.36.5

A second incantation describes a set of goddesses, including the one who bears Skanda:

mohī vimohī vimukhī guha-dhāriṇī ca nidrā ca devī virajās tu bhūtyai svāhā ॥ VP 6.37.9

Starting from its late Vedic roots, the association of Skanda with the mātṛ-s was remembered over a prolonged period in Indian historical tradition. For instance, it figures in the famous maṅgalācaraṇa of the Cālukya monarchs where they describe themselves thus: …mātṛ-gaṇa-paripālitānāṃ svāmi-mahāsena-pādānu-dhyātānām… Protected by the troop of mātṛ-s and meditating on the feet of lord Mahāsena. This association of a cluster of goddesses with Skanda is further developed in the Mahābhārata:

tataḥ saṃkalpya putratve skaṃdaṃ mātṛgaṇo .agamat ।

kākī ca halimā caiva rudrātha bṛhalī tathā ।

āryā palālā vai mitrā saptaitāḥ śiśumātaraḥ ॥ Mbh 3.217.9 (“critical”)

Having established the sonship of Skanda, the band of mātṛ-s went away: Kākī, Halimā, Rudrā, Bṛhalī, Āryā, Palālā and Mitrā, these are the seven mothers of Śiśu.

A similar list is given in the “mega”-Skandapurāṇa:

kākī ca hilimā caiva rudrā ca vṛṣabhā tathā ।

āryā palālā mitrā ca saptaitāḥ śiśumātaraḥ ॥ SP-M 1.2.29.175-76

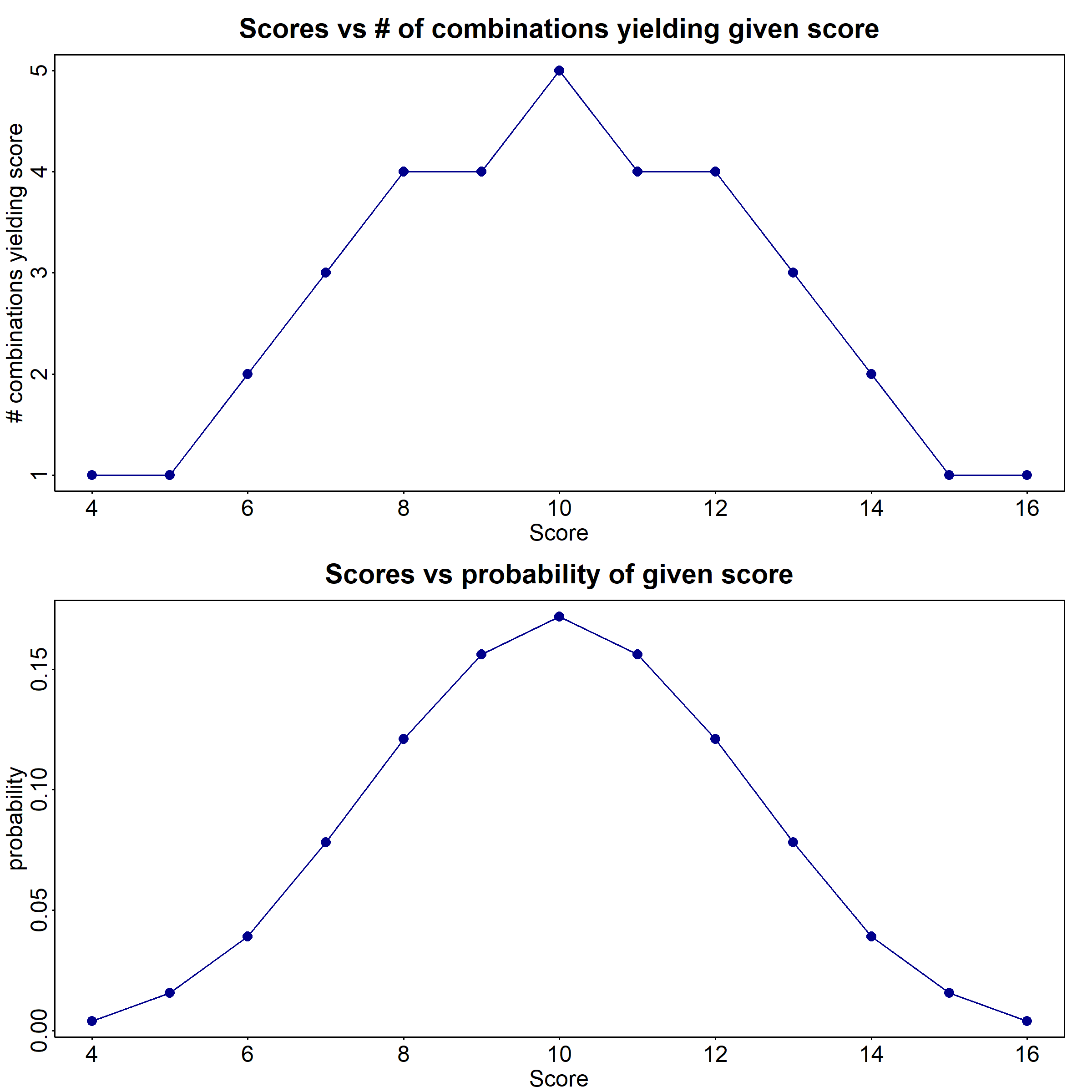

Notably, in this cluster of goddesses, we see, for the first time, an explicit list of 7 mātṛ-s — a number that became characteristic of the classical group of mātṛkā-s. In subsequent narrations of the Kaumāra cycle in the medical and paurāṇika traditions, the number of mātṛ-s who accompany Skanda is numerous and varied. Nevertheless, one of the archaic versions from the Mbh we encounter for the first time the description of these mātṛ-s as having the form of female versions of the gods:

yāmyo raudryas tathā saumyāḥ kauberyo .atha mahābalāḥ ।

vāruṇyo .atha ca māhendryas tathāgneyyaḥ paraṃtapa ॥

vāyavyaś cātha kaumāryo brāhmyaś ca bharatarṣabha ।

vaiṣṇavyaś ca tathā sauryo vārāhyaś ca mahābalāḥ । [missing in some recensions]

vaiṣṇavyo .atibhayāś cānyāḥ krūrarūpā bhayaṃkarāḥ । [Alternative for above]

rūpeṇāpsarasāṃ tulyā jave vāyusamās tathā ॥ Mbh 9.45.35-36

O scorcher of foes, possessed of great might [these goddesses took the forms] of Yama, Rudra, Soma, Kubera, Varuṇa, the great Indra and Agni. O bull among the Bharata-s, yet others of great might took the form of Vāyu, Kumāra, Brahman, /Viṣṇu, Sūrya, Vārāhī/Viṣṇu and other terrifying and fierce forms evoking great terror./ Endowed with the beauty of Apsaras-es, they were possessed of the speed of wind.

Thus, within this Kaumāra context, we see the first expression of a matṛ list converging on the classical system. Kaumāra-mātṛ-s appear first in iconography in the company of Skanda in Kuṣaṇa and pre-Kuṣaṇa sites like the holy city of Mathura. Even the earliest iconographic exemplars of the 7 classical mātṛ-s are connected to Skanda (Gupta age; see also the Patna inscription which speaks of Kumāragupta’s brother-in-law installing a shrine for Skanda at the head of the matṛ-s). However, in the post-Gupta age, the connection of Kumāra and the classical mātṛ-s gradually faded away. However, the old Vedic template of a multiplicity of goddesses in the company of a single god continued to be expressed. Among the gods of taking the place of Skanda in the mātṛkā panels were Kubera, Rudra, both in his classic form and as Tumburu, Vīrabhadra and Gaṇeśa. Of these, as we have noted before, the association with Rudra is archaic, having Vedic roots. It is reiterated in the Mbh:

vanaspatīnāṃ pataye narāṇāṃ pataye namaḥ ।

mātṝṇāṃ pataye caiva gaṇānāṃ pataye namaḥ ।

apāṃ ca pataye nityaṃ yajñānāṃ pataye namaḥ ॥ Mbh 7.173.38

Salutations to the lord of the trees, men, the mātṛ-s, the gaṇa-s, the waters, and ever the lord the rituals.

Indeed, a large host of 190 ferocious therocephalic and avicephalic mātṛkā-s, comparable to those accompanying Skanda, is described as being generated by Rudra to drink up the blood of Andhaka in the Matsyapurāṇa. In the same narrative, Nṛsiṃha also generates 32 mātṛkā-s to pacify the former. These latter goddesses are the arṇa-devī-s of the famed 32-syllabled mantra of Nṛsiṃha. A band of piśācī-s, who eat up the corpse of the daitya Hālāhala killed by the gaṇa-s of Nīlalohita-rudra, when he comes to take the skull of Brahman, are also known as Kapālamātṛ-s and associated with Rudra as per the proto-Skandapurāṇa (7.15-23). The association between Rudra and the mātṛkā-s is also emphasized in the historical record by the famous Gupta age inscription from Bagh, Madhya Pradesh, which mentions the Pāsupata teacher, Lokodadhi, installing a temple that is the station of the mātṛ-s in the village of Piñcchikānaka: … bhagaval lokodadhi pāsupatācārya-pratiṣṭhāpitaka-piñcchikānaka-grāma-mātṛ-sthāna-devakulasya … In conclusion, the conceptualization of the mātṛkā-s in the classical religion can be traced back to the Vedic layer of the religion, with an organic evolution in the Mahābhārata and the early medical literature, and close associations to the Kaumāra and Śaiva sects.

Cāmuṇḍā, her distinctness, and preeminence

Cāmuṇḍā from a prayoga manual from Nepal

However, there is one mysterious mātṛkā in the classical list who does not fit the general deva-patnī prototype inherited from the śruti. She goes by the common name Cāmuṇḍā or is alternatively known as Bahumāṃsā in some early paurāṇika texts. She is often distinguished by a corpse-, an owl- (e.g., Paraśurāmeśvara temple in Kaliṅga) or a vulture (the Mayamata pratiṣṭhātantra of saiddhāntika tradition) ensign. While she is explicitly linked to Rudra, she is often distinguished from his typical female counterpart Rudrāṇī. Cāmuṇḍā does not occur in any Vedic text (except in masculine form in a late addendum to the Vaikhānasa-mantra-praśna); nor does she occur in the epics.

In contrast, she appears profusely in paurāṇika texts. However, even here, in one of her early occurrences, directly pertaining to one of her holiest shrines, Koṭivarṣa, she is presented under a different name, Bahumāmsā, which appears to be a euphemistic double entendre. An apparently archaic version of the Koṭivarṣa-māhātmya, the famous pīṭha in Vaṅga, also known as Devīkoṭa (see below), was incorporated into the “proto”-Skandapuraṇa. Briefly, the frame story goes thus: Brahman once performed saṁdhyā at the Bay of Bengal for a crore years. Then he founded a beautiful city that eventually came to be known as Koṭivarṣa, where people lived a youthful existence. Once the god left the city, it was invaded by daitya-s, who committed many atrocities and slew thousands of brāhmaṇa-s and desecrated rituals. To remedy this, the gods went to Brahman and with him they went to Rudra. There Gaurī was performing tapasya in a grove and turned all the gods into females. Rudra then told them that they could slay the daitya-s only in their female forms. Thus:

tato devo .asṛjad devīṃ rudrāṇīṃ mātaraṃ subham ।

vikṛtaṃ rūpam āsthāya dvitīyām api mātaram ।

nāmnā tu bahumāṃsāṃ tāṃ jagat-saṃhāra-rūpiṇīm ॥

niyogād devadevasya tato viṣṇur api prabhuḥ ।

mātarāv asṛjad dve tu vārāhīṃ vaiṣṇavīm api ॥

abhūt pitāmahād brāhmī śarvāṇī saṃkarād api ।

kaumārī ṣaḍmukhāc cāpi viṣṇor api ca vaiṣṇavī ।

vārāhī mādhavād devī māhendrī ca puraṃdarāt ॥

sarvatejomayī devī mātṝṇāṃ pravarā subhā ।

bahumāṃsā mahāvidyā babhūva vṛṣabhadhvajāt ॥

sarveṣāṃ devatānāṃ ca dehebhyo mātaraḥ subhāḥ ।

svarūpabaladhāriṇyo nirjagmur daitya-nāsanāḥ ॥

vāyavyā vāruṇī yāmyā kauberī ca mahābalā ।

mahākālī tathāgneyī anyās caiva sahasrasaḥ ॥

tā gatvā tat puraṃ ramyaṃ daityān bhīmaparākramān ।

jaghnur bahuvidhaṃ devyo ghoranādair vibhīṣaṇaiḥ ।

daityahīnaṃ ca tac cakruḥ purāgryaṃ hemabhūṣitam ॥ “proto”-KM17-23

Then the god (Rudra) generated the goddess, mother Rudrāṇī. Taking an auspicious yet grotesque form, he also generated a second mother going by the name Bahumāṃsā, she of world-destroying form. At the mandate of the god of the gods, the mighty Viṣṇu also generated two mothers, Vārāhī and Vaiṣṇavī. From the Grandfather came Brāhmī and from Śaṃkara [came] Śarvāṇī. Kaumārī from Skanda (note irregular saṃdhi: ṣaḍmukhāt similar to that found in the Kaulajñānanirṇaya of Matsyendra. This supports the archaic nature of this narrative). Vārāhī from Mādhava and goddess Māhendrī from the smasher of forts (Indra). All these foremost of mothers were full of luster and auspicious. Bahumāṃsā, the great wisdom goddess, came into being from the bull-bannered one (Rudra). From the bodies of all these deities emerged auspicious mothers, each bearing their respective form and might, and set forth for the destruction of the demons: Vāyavyā, Vāruṇī, Yāmyā, Kauberī, Mahākālī, then Āgneyī of great strength, and thousands of others. The manifold goddesses slew [the demons], uttering terrifyingly ferocious yells. They made that foremost city decorated with gold free of the demons.

On one hand, the mātṛkā-s of narrative are reminiscent of the older Kaumāra cycle, and the Vedic Patnīsaṃyāja in naming a more inclusive set of goddesses including those generated by Vāyu, Varuṇa, Agni, etc. On the other hand, the core set of goddesses, who are named first, has crystallized to the classical 7-mātṛkā list. The only difference is that Bahumāṃsā replaces Cāmuṇḍā. However, their equivalence is clear from the account as Rudra specifically assumes a grotesque to generate her. As the narrative continues, Bahumāṃsā’s preeminent place in Koṭivarṣa is made amply clear:

hetukeśvara-nāmāhaṃ sthāsyāmy atra varapradaḥ ।

yuṣmābhiḥ saha vāsyāmi nāyakatve vyavasthitaḥ ॥

yas tu yuṣmān mayā sārdhaṃ vidhivat pūjayiṣyati ।

sarva-pāpavimuktātmā sa parāṃ gatim āpsyati ॥

dānavā nihatā yasmāc chūlena bahumāṃsayā ।

śūlakuṇḍam idaṃ nāmnā khyātaṃ tīrthaṃ bhaviṣyati ॥

iha sūlodakaṃ pītvā bahumāṃsām praṇamya ca ।

avadhyaḥ sarva-hiṃsrāṇām bhaviṣyati narottamaḥ ॥ “proto”-KM29-32

Under the name of Hetukeśvara, I (Rudra) will station myself here as the boon-giver. I will stay with you all, taking the position of leadership. Whoever worships you all together with me as per the ritual injunctions shall become free of sins and attain the highest state. From the trident with which Bahumāṃsā slew the demons, this holy pond will be known by the name of Śūlakuṇḍa. He who drinks the Śūla-water here and worships Bahumāṃsā will become unassailable to all harm-doers and will become the foremost of men.

Keeping with the preeminence of Bahumāṃsā in the early Koṭivarṣa cycle, in a subset of her early paurāṇika occurrences, Cāmuṇḍā appears independently of the classical mātṛkā lists. For example, Cāmuṇḍā is described in the Varāhapurāṇa as the slayer of the danava Ruru independently of the classical mātṛkā-s. This episode with the specific etymology furnished therein for the name Cāmuṇḍā (see below) is also told in the Devīpurāṇa in an expanded form (DP 83-88). However, in the DP version, Cāmuṇḍā is presented as one of the 7 classical mātṛkā-s. The slaying of Ruru is also retold in the Mātṛsadbhāva, an auxiliary text of the Brahmayāmala tradition. While other mātṛ-s are mentioned therein as being in the company of Rudra as Hetuka Bhairava (Hetukeśvara in the KM narrative), the main protagonist is Cāmuṇḍā in the form of Karṇamoṭī (Karṇamoṭinī), who pursues Ruru into pātāla and slays him after a battle lasting a crore years. This is used as an alternative etymology for Koṭivarṣa. The same text also mentions that Rudra emanated the goddess Ekavīrī from his forehead (third eye; note the Athena motif shared with the Greeks) to slay the daitya Dāruka. In the Cera country, the cult of Rurujit is widespread and closely associated with that of Bhadrakālī, who is described as the slayer of Dāruka. Indeed, the Brahmayāmala tradition preserved in south India tends to equate Bhadrakālī, the killer of Dāruka, with Cāmuṇḍā: bhadrakāli tu cāmuṇḍā sadā vijaya-vardhinī ॥ Interestingly, while the Mātṛsadbhāva’s focus is Koṭivarṣa, its extant manuscripts are found in the Cera country, suggesting that the cult was carried south from Vaṅga after the destruction of Devīkoṭa by the Meccan demons. Below we provide the account of the slaying of Ruru from the Varāhapurāṇa 96:

tasyā hasantyā vaktrāt u bahvayo devyo viniryayuḥ ।

yābhir viśvam idaṃ vyāptaṃ vikṛtābhir anekaśaḥ ॥

pāśāṅkuśadharāḥ sarvāḥ sarvāḥ pīnapayodharāḥ ।

sarvāḥ śūladharā bhīmāḥ sarvāś cāpadharāḥ śubhāḥ ॥

tāḥ sarvāḥ koṭiśo devyas tāṃ devīṃ veṣṭya saṃsthitāḥ ।

yuyudhur dānavaiḥ sārdhaṃ baddhatūṇā mahābalāḥ ॥

kṣaṇena dānava-balaṃ tat sarvaṃ nihatantu taiḥ ।

devāś ca sarve sampannā yuyudhur dānavaṃ balam ॥

kālarātryā balañ caiva yac ca devabalaṃ mahat ।

tat sarvaṃ dānava-balam anayad yama-sādanam ॥

eka eva mahādaityo rurus tasthau mahāmṛdhe ।

svāñ ca māyāṃ mahāraudrīṃ rauravīṃ visasarja ha ॥

sā māyā vavṛdhe bhīmā sarva-deva-pramohinī ।

tayā vimohitā devāḥ sadyo nidrāntu bhejire ॥

devī ca triśikhenājau taṃ daityaṃ samatāḍayat ॥

tayā tu tāḍitasyāsya daityasya śubhalocane ।

carma-muṇḍe ubhe samyak pṛthagbhūte babhūvatuḥ ॥

rurostu dānavendrasya carma-muṇḍe kṣaṇādyataḥ ।

apahṛtyāharad devī cāmuṇḍā tena sā ‘bhavat ॥

sarvabhūta-mahāraudro yā devī parameśvarī ।

saṃhāriṇī tu yā caiva kālarātriḥ prakīrtitā ॥

As she [Rudrāṇī] laughed, from her mouth arose numerous goddesses with many strange forms, by whom this universe was enveloped. These terrifying and auspicious goddesses all held lassos, goads, tridents, and bows, and all had full breasts. All those crores of mighty goddesses stood surrounding the [primary] goddess, bearing quivers, together fought with the dānava-s. The whole dānava force was rapidly assaulted by those [goddesses], and together with them, the gods fought the dānava force. The great deva-force, together with the army of Kālarātri, sent the entire dānava force to Yama’s abode. The great daitya Ruru stood alone in the great battle. He then released his terrible rauravī magic. That terrible all-god-deceiving magic grew, and, overcome by it, the gods immediately fell asleep. Then the goddess struck the daitya on the battlefield with her trident. Thus, struck by the beautiful-eyed goddess, the skin and the head of the daitya were cleanly separated. As the goddess instantly seized and took away the skin and the head of the lord of the dānava-s, she came to be known as Cāmuṇḍā. From the terrifying form of the supreme goddess that destroys all beings, she came to be known as Kālarātrī.

The text then provides the below praise of Raudrī, where she is clearly identified as Cāmuṇḍā:

jayasva devi cāmuṇḍe jaya bhūtāpahāriṇi ।

jaya sarvagate devi kālarātre namo’stu te ॥

viśvamūrte śubhe śuddhe virūpākṣi trilocane ।

bhīmarūpe śive vedye mahāmāye mahodaye ॥

manojave jaye jambhe bhīmākṣi kṣubhitakṣaye ।

mahāmāri vicitrāṅge jaya nṛtyapriye śubhe ॥

vikarāli mahākāli kālike pāpahāriṇī ।

pāśahaste daṇḍahaste bhīmarūpe bhayānake ॥

cāmuṇḍe jvālamānāsye tīkṣṇadaṃṣṭre mahābale ।

śata-yāna-sthite devi pretāsanagate śive ॥

bhīmākṣī bhīṣaṇe devi sarvabhūtabhayaṅkari ।

karāle vikarāle ca mahākāle karālini ।

kālī karālī vikrāntā kālarātri namos’tu te॥

In the above cycles, Cāmuṇḍā is identified with Rudrāṇī and also as the primary dānava-slaying goddess, a role otherwise performed by Durgā. A folk memory of this was probably prevalent throughout the Indosphere and is today mainly seen in South India (e.g., the Cera country or Mysuru in the Karṇāṭa country). Additionally, Cāmuṇḍā is also presented as a distinct goddess, who is part of Rudra’s retinue, independently of the other mātṛka-s. This being a popular position is established by multiple such references in post-Gupta kāvya. In one such, she is paired in her skeletal form with the equally skeletal gaṇa Bhṛṅgiriṭi in a beautiful Śārdūlavikrīḍita verse of Yogeśvara regarding the celebration in Rudra’s retinue of the birth of Skanda:

devī sūnum asūta nṛtyata gaṇāḥ kiṃ tiṣṭhatety udbhuje

harṣād bhṛṅgariṭāvayācita-girā cāmuṇḍayāliṅgite ।

avyād vo hata-dundubhi-svana-ghana-dhvānātiriktas tayor

anyonya-pracalāsthi-pañjara-raṇat-kaṅkāla-janmā ravaḥ ॥ Subhāṣita-ratna-kośa 5.1

The goddess [Rudrāṇī] has birthed a son. O gaṇa-s rise up and dance!

Why? From joy, Bhṛṅgiriṭi raising his arms sings unasked embraced by Cāmuṇḍā.

On top of the loud din from the beating of the resounding drums

is the rattling born of the bones from the skeletal cages of those two — may it protect you!

She is also praised as the goddess slaying Niśumbha by Bhavabhūti in another masterly Śārdūlavikrīḍita with an allusion to the famous axial motif:

sāvaṣṭambha-niśumbha-saṃbhramanamad-bhūgola-niṣpīḍana-

nyañcat-karpara-kūrma-kampa-vicaṭad-brahmāṇḍa-khaṇḍa-sthiti ।

pātāla-pratimalla-galla-vivara-prakṣipta-saptārṇavaṃ

vande nandita-nīlakaṇṭha-pariṣad-vyakta-rddhi vaḥ krīḍitam ॥ Subhāṣita-ratna-kośa 5.3

From your whirling of Niśumbha, the earth-globe, with the axis, is pressed,

down on the turtle’s shell shaking it, shattering the support of the universe’s hemisphere.

The seven oceans trying to flood the netherworld instead fall into your cavernous cheeks.

I praise your perfectly performed dance that delights the retinue of the blue-necked one.

*Also could be a double entendre for the pressed down foot.

While she is not explicitly named here, the cavernous cheeks indicate that the goddess being referred to is none other than Cāmuṇḍā (see below). The two notable points in this verse are: first, Rudra’s retinue is the audience for her dance, again suggesting that she is an integral part of it. Second, as we noted above, she is shown as assuming the role normally assigned to the goddess Durgā/Caṇḍikā, i.e., killing Niśumbha, again reinforcing the idea of a folk memory of Cāmuṇḍā as the primary demon-slayer. This overlap with Caṇḍikā will be further explored below.

Cāmuṇḍā also occurs independently of the classical mātṛkā list but as part of other clusters of goddesses in certain paurāṇika and tāntrika traditions, e.g., the Dakṣa-yajña episode at the beginning of the Mega-Skandapurāṇa (1.1.3.49-53; Māheśvara-khaṇḍa, Kedāra-khaṇḍa):

vīrabhadro mahābāhū rudreṇaiva pracoditaḥ ।

kālī kātyāyanīśānā cāmuṇḍā muṇḍamardinī ॥

bhadrakālī tathā bhadrā tvaritā vaiṣṇavī tathā ।

nava-durgādi-sahito bhūtānāṃ ca gaṇo mahān ॥

śakinī ḍākinī caiva bhūta-pramatha-guhyakāḥ ।

tathaiva yoginī-cakraṃ catuḥṣaṣṭyā samanvitam ॥

nirjagmuḥ sahasā tatra yajñavāṭaṃ mahāprabham ।

vīrabhadra-sametā ye gaṇāḥ śatasahasraśaḥ ॥

pārṣadāḥ śaṃkarasyaite sarve rudra-svarūpiṇaḥ ।

pañcavaktrā nīlakaṇṭhāḥ sarve te śastrapāṇayaḥ ॥

Impelled by Rudra himself, the mighty-armed Vīrabhadra marched forth right away to the grove of the yajña with Kālī, Kātyāyanī, Īśānā, Cāmuṇḍā, Muṇḍamardinī, Bhadrakālī, Bhadrā, Tvaritā and Vaiṣṇavī, the nine Durgā-s and the rest: the great bhūta-gaṇa-s, Śakinī, Ḍākinī, the ghosts, pramatha-s and Kubera-s agents (guhyaka-s). The circle of 64 yoginī-s also accompanied him. Hundreds of thousands of gaṇa-s accompanied Vīrabhadra. These troops of Śaṃkara all had the form of Rudra, with five heads, blue-throats, and weapons in their hands.

The mention of the nine Durgā-s, after the list of nine goddesses, implies that these nine, including Cāmuṇḍā, are those Durgā-s. The remaining mātṛkā-s (barring Vaiṣṇavī, who is also counted among the nine Durgā-s) are not featured in this list. Similarly, in the iconographic section of the Agnipurāṇa (a similar account is also found in the iconographic manual, the Pratiṣṭhā-lakṣaṇa-sāra-samuccaya), we encounter a tradition, where multiple Cāmuṇḍā-s are presented as part of a group of 8 cremation-ground mothers, the Ambāṣṭaka, again almost entirely distinct from the classical mātṛkā-s (AP 50.30-37):

kapāla-kartarī-śūla-pāśa-bhṛd yāmya-saumyayoḥ ॥

gaja-carma-bhṛd ūrdhvāsya pādā syāt rudracarcikā ।

Rudracarcikā [is depicted] holding a skull, battle scissors, trident, lasso to the right and left. She holds an elephant hide, and her leg is raised up.

saiva cāṣṭabhujā devī śiro-ḍamarukānvitā ।

tena sā rudracāmuṇḍā nāṭeśvary atha nṛtyatī ॥

Rudracāmuṇḍā is verily the eight-handed goddess holding a severed head and a ḍamaru. She is shown dancing as the goddess of the dance (c.f. the above verse of Bhavabhūti).

iyam eva mahālakṣmī-rupaviṣṭā caturmukhī ।

nṛ-vāji-mahiṣebhāṃś ca khādantī ca kare sthitān ॥

The goddess Mahālakṣmī is indeed shown in a four-faced form. She [is depicted] eating a man, horse, buffalo, and elephant held in her hands.

daśa-bāhus trinetrā ca śastrāsi-ḍamaru-trikaṃ ।

bibhratī dakṣiṇe haste vāme ghaṇṭāṃ ca kheṭakaṃ ॥

khaṭvāṅgaṃ ca triśūlañ ca siddha-cāmuṇḍakāhvayā ।

Siddha-cāmuṇḍakā is depicted, with ten arms and three eyes, bearing a weapon, a sword, a ḍamaru, a trident, in her right arms; a bell, a shield, a skull-topped brand and a trident in her left arms.

siddhayogeśvarī devī sarva-siddhapradāyikā ॥

etad rūpā bhaved anyā pāśāṅkuśayutāruṇā ।

The goddess Siddhayogeśvarī (the goddess of the kaula Pūrvāmnāya = Trika), who bestows all accomplishments, is shown with another form, crimson in color, holding a lasso and a hook.

bhairavī rūpa-vidyā tu bhujair dvādaśabhir-yutā ॥

Bhairavī, the beautiful wisdom goddess, is shown with 12 arms.

etāḥ śmaśānajā raudrā ambāṣṭakam idaṃ smṛtaṃ ।

These raudra [goddesses] of the cremation ground are known as the cluster of eight-mothers.

kṣamā śivāvṛtā vṛddhā dvibhujā vivṛtānanā ॥

Kṣamā is shown surrounded by jackals as an old female with two arms and a gaping mouth.

danturā kṣemakarī syād bhūmau jānukarā sthitā ।

The fanged Kṣemakarī is shown [seated] on the ground with her hands on her knees.

These Ambāṣṭaka goddesses, Rudracarcikā, Rudracāmuṇḍā, Mahālakṣmī, Siddha-cāmuṇḍā, Siddhayogeśvarī, Bhairavī, Kṣamā and Kṣemakarī are likely associated with the 8 mahāsmaśāna-s of the tāntrika tradition. This is supported by the presence of Mahālakṣmī in the list, who is associated with the mahāsmaśāna of Kollagiri or Lakṣmīvana (modern Kolhapur). In the list, we find two explicitly named Cāmuṇḍā-s, which hearkens back to the mega-Skandapurāṇa Navadurgā-s, where Cāmuṇḍā is followed by Muṇḍamardhinī, who on etymological grounds could be seen as the second Cāmuṇḍā. A third goddess of the Ambāṣṭaka, Kṣamā, is depicted as an old female with jackals — again, iconographically similar to Cāmuṇḍā. The ogdoad also features Rudracarcikā, another ectype of Cāmuṇḍā (see below). Thus, we have at least four goddesses in the Ambāṣṭaka group, who can be described as conforming to the Cāmuṇḍā type. This multiplicity hints at Cāmuṇḍā being worshiped as the primary goddess at several of the mahāsmaśāna-s.

Cāmuṇḍā with her husband Bhiṣaṇa-bhairava: the deities of Ekāmra (a Nepalian depiction)

At least one of these mahāsmaśāna-s featuring Cāmuṇḍā was perhaps located at Ekāmra (modern Bhubaneswar) in the Kaliṅga country. The association of Cāmuṇḍā with this site, along with her Bhairava consort and Kubera or his female counterpart Kauberī, is abundantly attested in the kaula tradition: tantra-s (e.g., Kubjikāmata) and prayoga manuals of the Paścimāmnāya (e.g., Siddhi-lakṣmī-kramārcanā-vidhi-s), the Uttarāmnāya traditions like Niśi-saṃcara, and Ḍāmara texts like the Tridaśa-ḍāmāra-pratyaṅgirā. For example, we have the below mantra-s from the Paścimāmnāya (or its combination with the Uttarāmnāya in the case of the last mantra) tradition:

aiṁ OṂ ekāmraka-mahākṣetra-bhīṣaṇa-mahā-bhairavāya yaṁ cāmuṇḍā-śakti-sahitāya ekapāda-kṣetrapālāya dhanādhipataye namaḥ ॥

OṂ aiṁ yaṁ raṁ laṁ vaṁ śaṁ ekāmrake ohāyī kālarātrī chippinī cāmuṇḍā kauberī । au-kṣaḥ (o-kṣaḥ) bhīṣaṇa-bhairava śrīpādukabhyāṃ namaḥ ॥

OṂ aiṁ yaṁ bhīṣaṇa-bhairavāya cāmuṇḍā-sahitāya ekāmraka-kṣetrādhipataye namaḥ ॥

OṂ ekāmrake kṣetre yaṃ bhīṣaṇabhairava yāṃ cāmuṇḍā ambāpāda khphreṁ ॥

Coming to Carcikā, her equivalence with Cāmuṇḍā is established by multiple sources. For example, Amarasiṃha in his lexicon says: karmamoṭī tu cāmuṇḍā carmamuṇḍā tu carcikā । (AK 1.1.92). The great Bhāskararāya Makhīndra reiterates this in his gloss on the Lalitā-sahasranāma. Consistent with this, we also have the Śārdūlavikrīḍita verse of Tuṅga, which mentions Carcikā in Rudra’s retinue, separately from Rudrāṇī, in a manner similar to Cāmuṇḍā, as noted above.

carcāyāḥ katham eṣa rakṣati sadā sadyo nṛ-muṇḍa-srajaṃ

caṇḍī-keśariṇo vṛṣaṃ ca bhujagān sūnor mayūrād api ।

ity antaḥ paribhāvayan bhagavato dīrghaṃ dhiyaḥ kauśalaṃ

kūṣmāṇḍo dhṛti-saṃbhṛtām anudinaṃ puṣṇāti tunda-śriyam ॥

How does he ever protect his garland of fresh human heads from Carcā?

Also his bull from Caṇḍī’s lion and his snakes from his son’s peacock?

Thus, wondering to himself about the lord’s deep mental skill

Kūṣmāṇḍa daily nourishes the growing satisfaction of his belly’s corpulence.

The presence of Carcikā in Rudra’s retinue, independently of the classical mātṛkā-s, is also seen in some paurāṇika traditions, such as the Vāmana-purāṇa (70 in vulgate; 45 in short edition). Here, in the final battle with Andhaka, Rudra then took all the gods and his gaṇa-s into his body (c.f. Greek Kronos motif). When Andhaka struck him with his mace and caused him to bleed, from his own blood, Rudra generated the 8 Bhairava-s. Then from his fertilizing sweat, Rudra generated the virgin goddess Carcikā from his forehead (c.f. Greek Zeus-Athena motif) and then Kuja (the planetary archon of Mars) from his sweat that dropped on the ground. Together, Carcikā and Kuja drank up the blood of Andhaka. This myth, with Carcikā drinking up the blood of Andhaka, is widely depicted in images throughout India.

Finally, Carcikā replaces Cāmuṇḍā in some classical 7/8 mātrikā lists in tāntrika mantra-prayoga-s, like those in the Hāhārava or the Picumata of the Brahmayāmala tradition. Below are the famed Aṃbāpāda mantra-s of the Hāhārava belonging to the Atharvaṇa-guhyakālī tradition (Uttarāmnāya), where the 8 classical mātṛkā-s are associated with the eight Bhairava-s and manifest as Kālī-s, each surrounded by a retinue of 64 yoginī-s:

OṂ hrīṃ huṃ chrīṃ phreṃ [bhairava] +āsanāya aṣṭāṣṭaka-yoginī-sahitāya [devī] kāli 2 aṃbāpāda huṃ phreṃ namaḥ ।

Asitāṅga-bhairava : Brahmavatī

Ruru-bhairava : Rudravatī

Caṇḍa-bhairava : Kumāravatī

Krodha-bhairava : Viṣṇumatī

Unmattabhairava : Ghoraṇavatī/Varahāvatī

Kapāla-bhairava : Mahendravatī

Bhīṣaṇa-bhairava : Carcikāvatī

Saṃhāra-bhairava : Mahālakṣmīvatī

OṂ hrīṃ hūṃ chrīṃ phreṃ muṇḍinyai [devī] 2 aṃbāpada chreṃ hūṃ namaḥ ॥

devī= Kālī, Mudgalā, Daṃṣṭrinī, Śṛṅgārā, Śūlinī, Vajriṇī Pāśinī, Aṃkuśinī

Carcikā is associated with two great shrines at the Western and Eastern extremities of India, respectively Hiṅgulā (Vamanapurāṇa vulgate 70.47) and Koṭivarṣa. Of these, Koṭivarṣa in the Vaṅga country is explicitly known as a mahāsmaśāna. Hence, we may identify Rudracarcikā, who heads the Ambāṣṭaka list, as the goddess associated with this site. In support of this proposal, we have the famous Vaṅgīya inscriptions found in the vicinity that specifically mention the shrines of Carcikā (e.g., the Siyān and Bangarh inscriptions). The Parbatiya inscription of the Vanamālavarman, the king of Assam in the 800s of CE, also mentions the renovation of the temple of Hetukeśvara, the Rudra associated with Koṭivarṣa. King Nayapāla (r. 1043–1058 CE) says that he built a temple for the image of Carcikā his ancestor, emperor Mahendrapāla (r. 845–860 CE), had installed:

… mahe[ndra]pāla-carcāyā mahendra-sadṛśodayaḥ । yaḥ śailīm vaḍabhīm śaile sopānena sahākarot …

He who presented like Mahendra built for Mahendrapāla’s Carcā a stone vaḍabhī temple on the hill with steps [leading to it] (Siyan inscription, unfortunately, damaged by the Meccan demons).

The saiddhāntika-śaiva-deśika, Mūrtiśiva, a preceptor of the Pāla monarchs, mentions that he installed a similar temple for Carcikā and worships her in two verses, in anuṣṭubh and śārdūlavikrīḍita, thus:

OṂ namaś carcikāyai ।

surāsuraśiraḥ-śreṇi-paṭa-vāsa-samā jagat ।

pāntu viśvakṛtābhyarcāś carcā-caraṇa-reṇavaḥ ॥

daṃṣṭrā-saṃdhi-nilīnam eka-kavalam viśvaṃ tad aśnāmi kiṃ?

saptāmbhodhi-jalāni hasta-suṣire guptāni kim pīyate ?

ity āhāra-daridratākulatayā śuṣyat tanum bibhratī

kalpānte nṛ-kapāla-maṇḍana-vidhiḥ pāyāj jagac carcikā ॥ (Bangarh inscription)

Obeisance to Carcikā.

Like perfumed powder for the turbans of the array of gods and demons,

worshiped by the world-maker (Viśvakarman), may the dust from Carcā’s feet protect the world.

“The universe is a single morsel that will lodge in space between my teeth. Then what shall I eat?

The waters of the seven oceans will be hidden in the hollow of my palm. Then what may be drunk?”

Thus, anxious from the poverty of her meal, with her body becoming desiccated, observing,

at the end of the age, the rite wearing a garland of human heads, may Carcikā protect the world.

In the above verse, one may note the parallel to the drinking of the oceans seen in Bhavabhūti’s verse cited above. In addition, Koṭivarṣa, the same region of Vaṅga (Varendrī) also had another famous Cāmuṇḍā shrine, Puṇḍravardhana, which is mentioned along with Ekāmra by the great Kashmirian mantravādin Abhinavagupta in his Tantrāloka. The Uttarāmnāya has the below incantation remembering this now lost site:

OṂ hrīṃ śrīm śrī-puṇḍravardhana-mahopakṣetre cāmuṇḍā ambāpāda khpreṃ namaḥ ।

Pāla Carcikā

The recovery of at least 24 images of the ekavīrā type, i.e., Carcikā or Cāmuṇḍā independently of other mātṛkā-s, from the Pāla age sites ruined by the Mohammedans, in the vicinity of Koṭivarṣa and Puṇḍravardhana, attests to the importance of her cult in the Varendrī region. One of these images is remarkable in depicting Carcikā, flanked by Gaṇeśa and the Bhairava or Mahākāla, surrounded by 20 Carcikā-s (totally with the central figure 21 goddesses; c.f. the 21 Tārā-s of the bauddha tradition). This multiplicity of Carcikā-s brings to mind the array of 20 Carcikā-s mentioned the Siddhāṅga-pañcaka-mantra-s of the Śaktisūtra:

ghasmarā carcikā vicceśvarī śrīviccāvvā- pāduke pūjayāmi aiṃ ॥

svarūpavāhinī nava-sthānagā śrīnandinī- viccāvvā pāduke pūjayāmi aiṃ ॥

padmā śobhā vikāśinī viccāvvā- pāduke pūjayāmi aiṃ ॥

mahāśāntā vikasvarā vikāśinī viccāvvā- pāduke pūjayāmi aiṃ ॥

nāda-carcikā śabdādyā śrīṣaṭkā viccāvvā- pāduke pūjayāmi aiṃ ॥

If we count the last goddess, Viccāvvā, who is the same in each of the five, then we get a list of 16 comparable to the 16 Cāmūṇḍā-s mentioned in the southern Brahmayāmala with roots in the Vaṅga country.

The scorpion-goddess

Vṛścikā from Prayāga

We next consider a goddess who is iconographically similar to Cāmūṇḍā but distinguished by a scorpion ornament on her belly. Images of this goddess are widely distributed across India, but a scorpion is never mentioned as an ornament in any of the numerous iconographic accounts of Cāmūṇḍā. Moreover, this scorpion goddess is only found in ekavīrā form, never with the other mātṛkā-s. To decipher who she is, we have to turn to the mega-Skandapurāṇa, which mentions scorpions as the medallion of Caṇḍī, a member of the entourage of Rudrasadāśiva:

tathodyato yoginī-cakra-yukto gaṇo gaṇānāṃ patir eka-varcasām ।

śivaṃ puraskṛtya tadānubhāvās tathaiva sarve gaṇanāyakāś ca ॥

tad yoginī-cakram ati-pracaṇḍaṃ ṭaṃkāra-bherī-rava-svanena ।

caṇḍī puraskṛtya bhayānakāṃ tadā mahāvibhūtyā sam-alaṃkṛtāṃ tadā ॥

kaṇṭhe karkoṭakaṃ nāgaṃ hāra-bhūtaṃ cakāra sā ।

padakaṃ vṛścikānāṃ ca dandaśūkāṃś ca bibhratī ॥

karṇā-vataṃsān sā dadhre pāṇi-pāda-mayāṃs tathā ।

raṇe hatānāṃ vīrāṇāṃ śirāṃsy urasi cāparān ॥

dvipi-carma-parīdhānā yoginī-cakra-saṃyutā ।

kṣetrapālāvṛtā tadvad bhairavaiḥ parivāritā ॥

tathā pretaiś ca bhūtaiś ca kapaṭaiḥ parivāritā ।

vīrabhadrādayaś caiva gaṇāḥ parama-dāruṇāḥ ।

ye dakṣa-yajña-nāśārthe śivenājñāpitās tadā ॥

tathā kālī bhairavī ca māyā caiva bhayāvahā ।

tripurā ca jayā caiva tathā kṣemakarī śubhā ॥

anyāś caiva tathā sarvāḥ puraskṛtya sadāśivam ।

gantu-kāmāś cogratarā bhūtaiḥ pretaiḥ samāvṛtāḥ ॥

Then the accompanied by the circle of yoginī-s, the gaṇa, the lord of the gaṇa-s (Nandin) of singular splendor and all the leaders of the gaṇa-s followed, keeping Śiva at their head. The circle of yoginī-s was most-terrifying and resounding with their yells, like the beating of kettledrums. They kept at their forefront the terrible Caṇḍī adorned with great magnificence. She had made the Karkoṭaka snake in the form of a necklace on her neck. She had a medallion of scorpions and bore snakes. Her earrings were made of severed hands and legs. She wore the severed heads of warriors slain in battle on her chest. She wore a skirt of elephant-hide and was accompanied by the circle of yoginī-s. She was surrounded by Kṣetrapāla-s and likewise by Bhairava-s. Similarly, she was accompanied by zombies, ghosts and deceiver ghosts. With Vīrabhadrā at their head, were the most-terrifying gaṇa-s, who had been ordered by Śiva to destroy Dakṣa’s sacrifice (the Raumya-s). Likewise, there were Kālī, Bhairavī, the frightful Māyā, Tripurā, Jayā and the auspicious Kṣemakarī. These and all others, of great ferocity, keeping Sadāśiva at their head, surrounded by ghosts and zombies, desired to march forth.

This is an account of the bridal procession of Rudra’s retinue on the occasion of his marriage to Pārvatī. Though he was displaying this sport of marrying his wife again following Sati’s reincarnation as Pārvatī, his Śakti-s never really left him. The chief among them is Caṇḍī, wearing a badge or medallion of scorpions. Thus, it appears that this ever-present Śakti of Rudra is depicted as the ekavīrā vṛścikodarī goddess. It is possible that the scorpion was identified with the eponymous constellation. Thus, its placement on the belly of the destroying goddess might have had an astronomical symbolism related to the constellation’s position at the southern point of the ecliptic (associated with her seasons: autumn/winter: right in the Yajurveda) and its connection to the Vedic goddess of the netherworld and doom, Nirṛti. In another account of the destruction of Dakṣa’s sacrifice from the Kāyāvarohaṇa-māhātmya (5.82), Rudrāṇī herself generates a goddess by rubbing her nose, who is described by the epithet śahasracaraṇodarī. This might be interpreted either as she with a 1000 feet and bellies or with a millipede on her belly, giving a possible parallel for this iconography.

Despite her widespread presence in Śaiva temples, the presence of this goddess in the mantra-śāstra is limited. The goddess Kubjikā is described as having scorpion ornaments like her husband Aghora in the prayoga-texts of the Kaula tradition (e.g., Ṣaḍāmnāyapūjāvidhi):

agni-jvālā-prabhābhair jvalana-śikhi-piccha-vṛścikair hāramālā ।

muṇḍasraṅ-muṇḍa-bhāgābhaya-durita-harā kubjikeśī namas te ॥

Obeisance to you. Goddess Kubjikā, who takes away misfortune has the glow of blazing flames, is garlanded by a wreath of shining peacock feathers and scorpions, and a garland of severed heads, holds a severed head, and shows the gestures of protection and boon-giving.

The scorpion-goddess Vṛścikā also figures in the Śrikula practice of the meditation on the six cakra-s along the path of the suṣuṃṇa. In the Anāhata-cakra, she is worshiped in the circle of the goddess Rākinī presiding over blood along with her Rudra. Here, she is worshiped along with several other goddesses, including Cāmuṇḍā, on the 12 spokes of the cakra. The Vaṅgīya mantravādin Pūrṇānanda explains it thus in his Tattvacintāmaṇi:

anāhate nyaset paścāt paritaḥ ka-ṭha-varṇakaiḥ ।

kālarātriḥ khātitā ca gāyatrī ghaṇṭikā tataḥ ॥

ṅā vṛścikā ca cāmuṇḍā chāyā jayā tathaiva ca ।

jhaṅkāriṇī tathā jñānā ṭaṅkahastā ca vinyaset ॥

ṭhaṅkārī ca kramādetā dhyātvā vīraśca pūrvavat ।

The equivalence between the goddesses and the bīja-s formed from the arṇa-s is thus: kaṃ: Kālarātriḥ; khaṃ: Khātitā; gaṃ: Gāyatrī; ghaṃ: Ghaṇṭikā; ṅaṃ: Vṛścikā; caṃ: Cāmuṇḍā; chaṃ: Chāyā; jaṃ: Jayā; jhaṃ: Jhaṅkāriṇī; ñaṃ: Jñānā; ṭaṃ: Ṭaṅkahastā;

ṭhaṃ: Ṭhaṅkārī.

This meandering discussion establishes that, while Cāmuṇḍā was seen as part of the 7/8 mātṛkā-s, she also had a separate existence either as a preeminent figure among the mātṛkā-s or as an independent goddess. In the latter capacity, she both iconographically and mythologically, overlapped with the domains of two independent goddesses Bhadrakālī and Caṇḍī/Caṇḍikā. An example of this overlap in folk tradition is the poem of Bhuṣaṇa Tripāṭhī on Śivājī, where he says that Caṇḍī is growing fat from eating the Mohammedans offered to her by the Marāṭhā advance — thus, he equates Caṇḍī to the emaciated Cāmuṇḍā.

Cāmuṇḍā’s place in the mantra-śāstra

We now turn to the mantraśāstra to examine some aspects of her worship. The KM already signals that the worship of the goddesses at Koṭivarṣa was according to the tantra-s known as the Yāmala-tantra-s:

ahaṃ brahmā ca viṣṇus ca ṛṣayas ca tapodhanāḥ ।

mātṛtantrāṇi divyāni mātṛ-yajñavidhiṃ param ।

puṇyāni prakariṣyāma yajanaṃ yair avāpsyatha ॥

brāhmaṃ svāyambhuvaṃ caiva kaumāraṃ yāmalaṃ tathā ।

sārasvataṃ sagāndhāram aiśānaṃ nandiyāmalam ॥

tantrāṇy etāni yuṣmākaṃ tathānyāni sahasrasaḥ ।

bhaviṣyanti narā yais tu yuṣmān yakṣyanti bhaktitaḥ ॥

narāṇāṃ yajamānānāṃ varān yūyaṃ pradāsyatha ।

divyasiddhipradā devyo divyayogā bhaviṣyatha ॥

yās ca nāryaḥ sadā yuṣmān yakṣyante sarahasyataḥ ।

yogesvaryo bhaviṣyanti rāmā divyaparākramāḥ ॥ KM 34-38

I [Rudra], Brahman, Viṣṇu and the sages with a wealth of tapas will compose the pure and divine Mātṛ-tantra-s [expounding] the foremost procedures for the rituals to the Mātṛ-s, by which you all would be worshiped. Brāhma, Svāyambhuva, Kaumāra-yāmala, Sārasvata with Gāndhāra, Aiśāna, Nandi-yāmala — these tantra-s of yours and thousands of others will come into being, and men will piously worship you all with them. You, O goddesses, endowed with divine yoga, will grant boons to the men who worship you and confer magical powers on them. Those women who will continuously worship you with the secret rituals will become the mistresses of yoga, beautiful and possessed of magical prowess.

Consistent with the above, the root tantra of the Brahmayāmala tradition, the Picumata, has a major section devoted to the yoginī-kula-s associated with each of the mātṛkā-s. Given the preeminence of Cāmuṇḍā at Koṭivarṣa, one would expect a special place for her among the mātṛkā-s in the mantra-śāstra. We believe that imprints of this are seen throughout the Śaiva- and Śākta- mantraśāstra and their arborizations. For example, the pratiṣṭhā-tantra, Mayamata, after giving the iconographic specifications for the 7 mātṛkā-s flanked by Vīrabhadra and Vināyaka, provides a second section only for Cāmuṇḍā. There it describes the installation of her images with 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, or 16 arms made from wood, clay, or stucco. It states they should show her dancing (see above) the twilight dance either by herself or place her beside Rudra, shown performing the same dance. It further mentions that the images with 4 or 6 arms are helpful for pacificatory purposes. It is again specified that the worship/festivals should be officiated as per the Yāmala-tantra-s (e.g., Southern Brahmayāmala).

The dominance of Cāmuṇḍā in the Śaiva systems is also apparent in the archaic mantra-śāstra recorded in the Ḍāmara-tantras. There, Cāmuṇḍā is invoked in a “fever-missile” incantation deployed to strike adversaries with a wasting fever thus:

OṂ bakāmukhā cāmuṇḍā kṣīra-māṃsa-śoṇita-bhojinī [amukaṃ] khaḥ khaḥ jvareṇa gṛhṇa gṛhṇa gṛhṇāpaya gṛhṇāpaya huṃ phaṭ svāhā ॥

Remarkably, the goddess is described as being heron-faced. While this is not encountered in any of her later extant iconographies, on one end, it connects her to the archaic avicephalous goddesses associated with Skanda in the early Kaumāra cycles and the avicephalous goddesses of the Kumārī (Kauśikī Vindhyavāsinī) cycle of the proto-Skandapurāṇa. On the other end, it connects her to the terminal Śaiva-śākta Mahāvidyā tradition, which features the attacking goddess Bagalāmukhī, whose name likewise means heron- or stork- headed. Bagalāmukhī too is not commonly shown with an avian head, but we have multiple prominent exemplars of such iconography in her case. First, we have such a painting from Kangra, Himachal. There is also the avicephalous Bagalāmukhī with 16 hands at the Saṇkaṭa Ghāṭa temple in Vārāṇasi. In a painting from the Bagalāmukhī temple at Bankhandi, Himachal, she is shown riding a crane, which also attacks the daitya whom she slays. Notably, at the Bagalāmukhī temple at Nīlācala, Assam, she is depicted with an owl ensign, another feature shared with Cāmuṇḍā. This suggests that grotesqueness of Cāmuṇḍā’s form included within it a long, iconographically unexpressed memory of the ancient avicephalous goddesses, which was subsequently passed on Bagalāmukhī. She is also identified with another of the Mahāvidyā-s, Chinnamastā, in the opening verse of her famous stotra, though their iconography is rather distinct:

OṂ chinnamastā mahāvidyā mahābhīmā mahodarī ।

caṇḍeśvarī caṇḍa-mātā caṇḍa-muṇḍa-prabhañjinī ॥

Her presence is also felt across the Śakti-para Śaiva systems. Kubjikā, the supreme goddess of the Paścimāmnāya, is seen as having several deities (Rudra and Dūtī-s) associated with her respective nyāsa aṅga-s:

Hṛdaya: Kālī

Śiras: Siddhayogeśvarī or Juṣṭācāṇḍālī

Śikhā: Svacchanda-bhairava (the deity of the Bahurūpī ṛk)

Kavaca: Śivā

Netra-traya: Raktacāmuṇḍā (Parā in some traditions)

Astra: Pratyaṅgirā or Guhyakālī

As one can see, the deity of the eyes of Kubjikā is none other Raktacāmuṇḍā. Her mantra is given as:

OṂ rakte mahārakte chāmuṇḍeśvarī svāhā ॥

aiṃ rakte mahārakte chāmuṇḍeśvarī khphreṃ svāhā ॥

The first is the root form and the second version is the kaula deployment.

Raktacāmuṇḍā’s deep presence is indicated by her presence in other Śaiva mantra traditions. For example, the Ḍāmara tradition deploys her mantra for the successful procurement of medicinal herbs:

OṂ hrīṃ raktacāmuṇḍe hūṃ phaṭ svāhā ॥

The Ḍāmara tradition also worships her in the company of Rudra as Nṛsiṃha, a feature shared with the Guhyakālī tradition:

OṂ hrīṃ śrīṃ klīṃ draṃ caṇḍogre trinetre cāmuṇḍe ariṣṭe hūṁ phaṭ svāhā । hrīṃ namāmy ahaṃ mahādevaṃ nṛsiṃhaṃ bhīmarūpiṇaṃ OṂ namas tasmai ॥

At the root of the Śākta tradition are the famed mantra-s of Cāmuṇḍā, the most fundamental of which is the Navārṇa-mantra. Tradition hails it as the best of the best of the Śākti-mantra-s: vicce navārṇa-mantro .ayaṃ śakti-mantrottamottamaḥ ।. It goes thus:

(OṂ) aiṃ hrīṃ klīṃ cāmuṇḍāyai vicce ॥

It might be expanded to include Cāmuṇḍā at the end of the mātṛkā-list as the Sarva-mātṝ-maya-mantra:

(OṂ) hrīṃ brahmāṇī-māheśvarī-kaumārī-vaiṣṇavī-vārāhī-aindrī-cāmuṇḍāyai vicce svāhā ।

We then have the Padamālā-mantra found in several texts like the Devīpurāṇa and the Yuddhajayārṇava-tantra (which in turn is included in Agnipurāṇa; AP 135). This long mantra, while including all the mātṛkā-s as the above, has as its primary deity the 28-handed Cāmuṇḍā. It ends with the mantra-pada:

OṂ cāmuṇḍe kili kili OṂ vicce huṃ phaṭ svāhā ॥

These mantra-s indicate the intimate connection between Cāmuṇḍā and the mysterious mantra utterance “vicce”. Indeed, Abhinavagupta even calls her Viccikā in his Tantrāloka, making one wonder if there is some connection to Vṛścikā via a Prākṛta form. In any case, the ending of the Padamālā-mantra is remarkably similar of the root mantra of the Paścimāṃnāya, the Samayāvidyā, which is the female counterpart of the Bahurūpī ṛk (the Aghora-brahma-mantra [Footnote 3]). Every syllable of the Samayāvidyā corresponds to one of the 32 syllables of the metrical Bahurūpī. The standard Paścimāṃnāya Samayāvidyā:

OṂ bhagavati ghore hskhphreṃ śrīkubjike hrāṃ hrīṃ hrauṃ ṅa-ña-ṇa-na-me aghoramukhi chrāṃ chrīṃ kiṇi kiṇi vicce ॥

The Paścimāṃnāya Samayāvidyā as per the Vaṅgīya tradition:

OṂ namo bhagavati hskhphreṃ hauṃ kubjike aiṃ hrīṃ srīṃ aghore ghore aghoramukhi klīṃ klīṃ kili kili vicce ॥

This suggests that the Cāmuṇḍā mantra influenced the construction of the Samayāvidyā.

Moreover, the Aṣṭa-mātṛkā-mantra-s of the Paścimāmnāya also parallel the Sarva-mātṝ-maya-mantra:

aiṁ aghore amoghe varade vimale [bīja] [devī] vicce ॥

śrīṃ: brahmāṇī; caṃ: kaumārī; ṭaṃ: vaiṣṇavī; thaṃ: vārāhī; paṃ: indrāṇī; yaṃ: cāmuṇḍādevī; śaṃ: mahālakṣmī

As noted above, we have the Śakti-sūtra of the Paścimāmnāya, which as has the Siddhāṅga-pañcaka-mantra-s to the array of Carcikā-s. Finally, a similar kind of influence of the Cāmuṇḍā mantra, likely via the Paścimāmnāya, is also seen on the construction of the long mantra of the erotic goddess Bhagamālinī of the Dakṣiṇāmnāya (note pada bhaga-vicche):

OṂ āṃ aiṂ bhagabhage bhagini bhagodari bhagāṅge bhagamāle bhagāvahe bhagaguhye bhagayoni bhaganipātini sarvabhage bhagavaśaṅkari bhagarūpe nityaklinne bhagasvarūpe sarvabhagāni me hyānaya varade rete surete bhagaklinne klinnadrave kledaya drāvaya amoghe bhaga-vicche kṣubha kṣobhaya sarvasattvān bhageśvari aiṃ blūṃ jaṃ blūṃ bheṃ moṃ blūṃ heṃ blūṃ ai/ blūṃ klinne sarvāṇi bhagāni me vaśamānaya strīṃ blūṃ hrīṃ bhagamālinī-nityā-kalāyai namaḥ ॥ (As per the Jñānārṇava–tantra 15)

The etymology of Cāmuṇḍā

Finally, we come to the peculiar issue of the etymology of Cāmuṇḍā. The Purāṇa-s offer multiple alternative “folk etymologies,” e.g., from carma+muṇḍa (Devī- and Varāha- purāṇa-s) or from Caṇḍa and Muṇḍa; however, none of these are by any means grammatical Sanskrit derivations. Moreover, the multiplicity also suggests that its actual roots were forgotten by the time the name was in common use. Yet, it seemed deserving of an explanation to the Sanskrit speaker as it did not seem “natural”, unlike the names of the other mātṛkā-s with deep Indo-Aryan roots. This goes with the fact that she is not a straightforward female counterpart of the gods, unlike most other mātṛkā-s.

Interestingly, some of her earliest mentions in the Koṭivarṣa-māhātmya and the Vindhyavāsinī section of the proto-Skanda-purāṇa, furnish her with a bivalent, but proper Sanskrit name, Bahumāṃsā. However, this name did not persist. Indeed, the other names of Cāmuṇḍā, Carcikā and Karṇamoṭī, or the peculiar mantra-pada vicce are also not attested in the earliest Sanskrit texts and lack a transparent Sanskrit etymology. This suggests that the names of this goddess adopted from a non-Aryan language eventually acquired wide currency within Sanskrit. This was hinted at even by Bhaskararāya. Moreover, as we noted above, Cāmuṇḍā overlaps with the domain of the related goddess known as Caṇḍī/Caṇḍikā, who is traditionally an ectype of Durgā. It does seem like Caṇḍī and Carcikā too might have originated from different attempts at Sanskritization of the same non-Aryan word that also gave rise to Cāmuṇḍā.

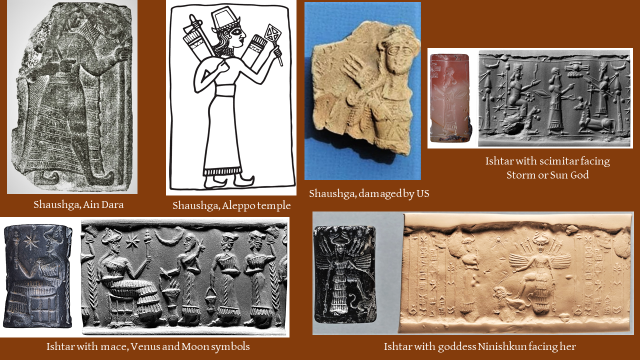

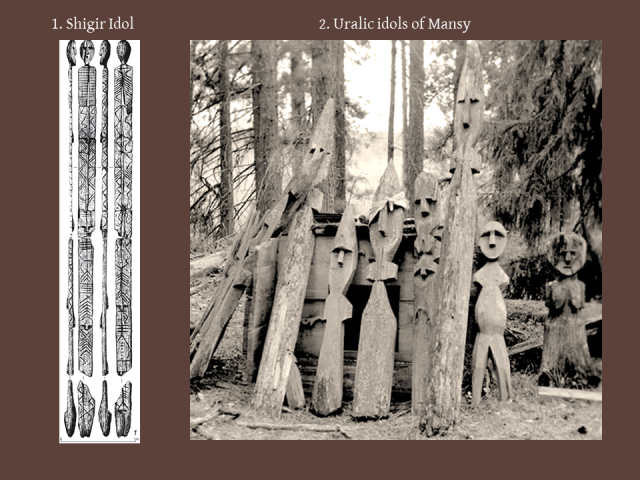

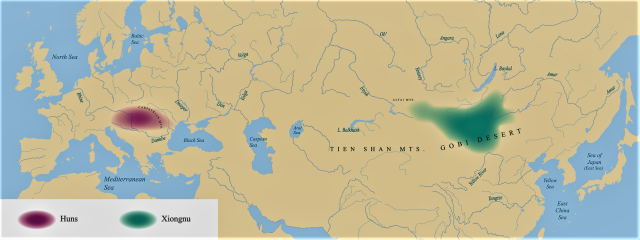

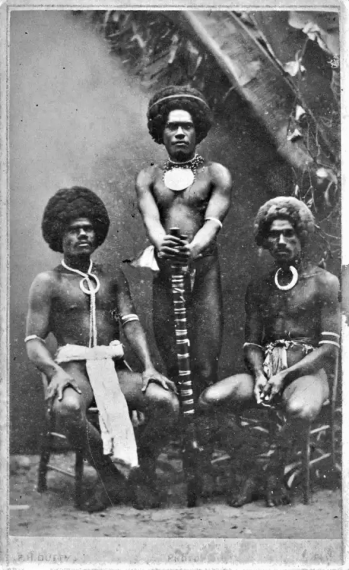

Its absence in the Vedic and epic layers of the language suggests that the word was unlikely to have been borrowed from a language the ārya-s encountered en route to India (Uralic or Bactria-Margiana) or upon first entering India (the Harappan language). We cannot etymologize it as Dravidian or Austro-Asiatic either. Hence, we have to tentatively admit that it might be from a now-extinct tribal language. Adopting such a name when an early Sanskrit name Bahumāṃsā was already in use suggests that simple syncretism with tribal goddesses was not at play. Instead, foreign words might be adopted to indicate special powers in incantations (e.g., the jharbhari-turphari sūkta to the Aśvins right in the RV itself). Thus, in the tāntrika tradition, the adoption of words from or which sound like from other languages is part of the same process. We posit that this was the mechanism by which the Navārṇa-mantra was constructed and, in turn, this made Cāmuṇḍā a more popular name displacing Bahumāṃsā. This also goes hand in hand with a widespread tendency to show the universality of the deity. In the case of the great Rudrian goddesses, this was also associated with a tendency to emphasize her links to the Rudrian domain of the exterior, which includes the tribal groups (already seen in the Yajurveda). This is also signaled by indicating the worship of the goddess in distant or non-Aryan lands. For instance, in the proto-Skandapurāṇa, the virgin goddess Kauśikī born of the black slough of Pārvatī emanated numerous avicephalous and therocephalous goddesses to aid her in the killing of Śumbha and Niśumbha. Thereafter, these goddesses were installed for worship in various countries, like the owl-headed Upakā in Pārasīka (Iran); the raven-headed Vāyasī in Yavana (Greek lands); the lion-headed Pracaṇḍā in Tukhara (Tocharia); Vānarī among the Śabara tribesmen; several others in the provinces of Lankā. This is reflected in the mantra-śāstra by the names of the goddesses like Gāndhārī or Dramiḍi.

Footnote 1: First appears as theonym of Tvaṣṭṛ in his aspect as Viśvakarman in RV 10.82.02. There Viśvakarman is explicitly described as Dhātṛ. The equivalence of Dhātṛ, Viśvakarman and Tvaṣṭṛ is established in the late Yajurvedic version of the Puruṣa-sūkta with the appendix termed the Uttaranārāyaṇa.

Footnote 2: This pattern is reproduced in the national epic on the earthly plane in the unusual polyandry of the five Pāṇḍava-s to Draupadī.

Footnote 3: The Kashmirian Kaṭḥa tradition preserves a form of the Bahurūpī that combines both the Rudra-s and the Rudrāṇī-s; recorded by the mantravādin Svāmin Lakṣmaṇa Jū

s, and the blue sky was that of Mitra and Varuṇa. In his breath he sensed Agni who runs the body. As the sunbeams fell on him through the leafy holes, he was profoundly impacted by how much of the sensed world was run by the Marut-s. Then a red twin-winged seed glided up to him bringing to mind the Aśvin-s, whom some of his ancestors also saw as Bhavā-Śarvau. Suddenly, he saw a great hawk, a sign of Suparṇo Garutmant: coursing through the welkin it passed out of sight against the backdrop of a distant mountain looming on the horizon. That brought to mind the mighty Indra, who in the days of yore had made those rocks find their resting place. As he passed a little stream, burbling as though uttering the triple vyāhṛti-s, he saw the sign of Sarasvatī. Recognizing her, he looked down at the path which he was walking on and obtained the sign of Pūṣan. This made him glance at the time and he sensed Viṣṇu who tramples all under his stride. Thus, wending his way, he passed a cluster of well-kept houses, built on the high, of carefree dhanin-s, who had been endowed by the roll of the dice of the King of the Guhyaka-s: in them, he saw the sign of King Aryaman. A little beyond those houses at the boundary of a wooded plot was a cemetery with a few tumbled-down gravestones signaling the presence of King Yama and Rudra. He silently uttered the incantation “namas te rudra manyava uto ta iṣave namaḥ । namas te astu dhanvane bāhubhyām uta te namaḥ ॥”. Reflecting on his recognition of the gods, he said to himself: “I see the sambandha-s just as our ārya ancestors or the sunthemata as the yavana-s would have called them.”

Figure 4. Zeus slaying the Gigantes with his thunderbolt.

Figure 4. Zeus slaying the Gigantes with his thunderbolt. Figure 5. Productions of the god Skanda by Stable Diffusion (Dec 7, 2022)

Figure 5. Productions of the god Skanda by Stable Diffusion (Dec 7, 2022) 1. Aditi engendering the Āditya-s

1. Aditi engendering the Āditya-s 2. The god Agni and the goddess Agnāyī emerging from the ritual fire

2. The god Agni and the goddess Agnāyī emerging from the ritual fire 3. The god Bhaga with his two consorts stabilizing Dyaus and Pṛthivī

3. The god Bhaga with his two consorts stabilizing Dyaus and Pṛthivī 4. The gods Bhava, Śarva and Rudra

4. The gods Bhava, Śarva and Rudra 5. The universal form of the goddess Indrāṇī: Viśvatomukhī

5. The universal form of the goddess Indrāṇī: Viśvatomukhī 6. The masked Kaumāra goddess Mukhamaṇḍikā

6. The masked Kaumāra goddess Mukhamaṇḍikā

Figure 3

Figure 3

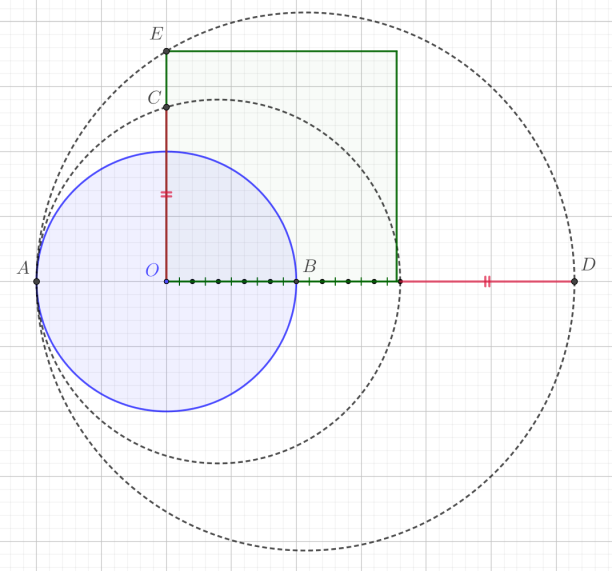

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Avicephalous and therocephalous Kaumāra goddesses from Kuśana age Mathurā

Avicephalous and therocephalous Kaumāra goddesses from Kuśana age Mathurā

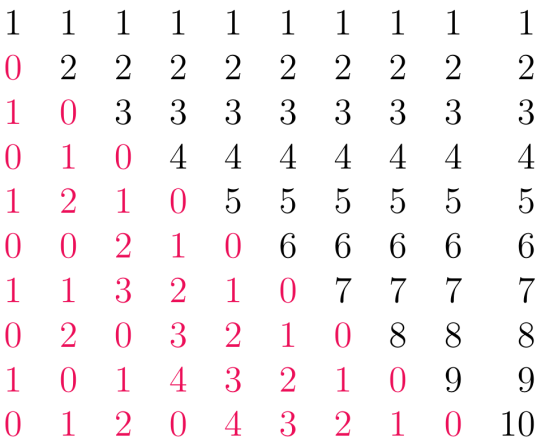

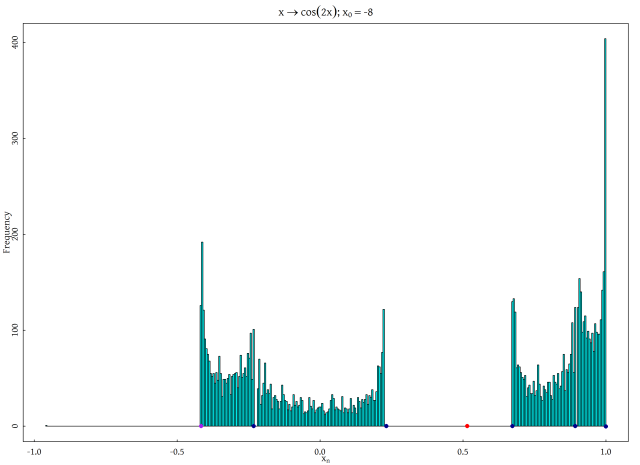

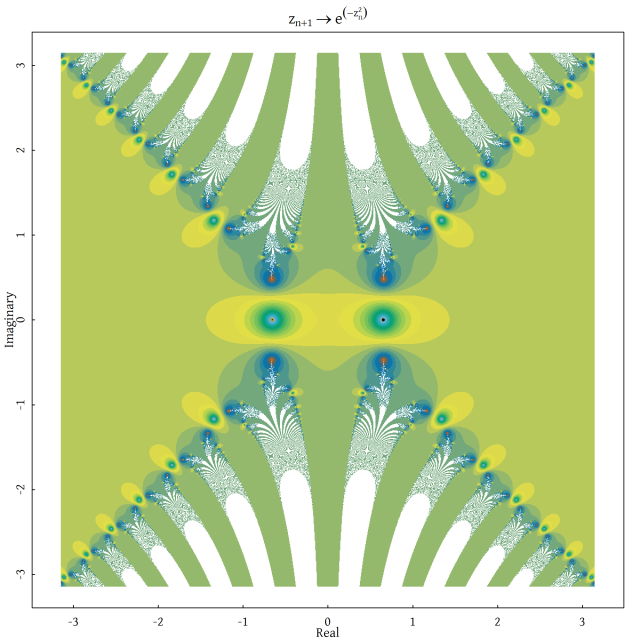

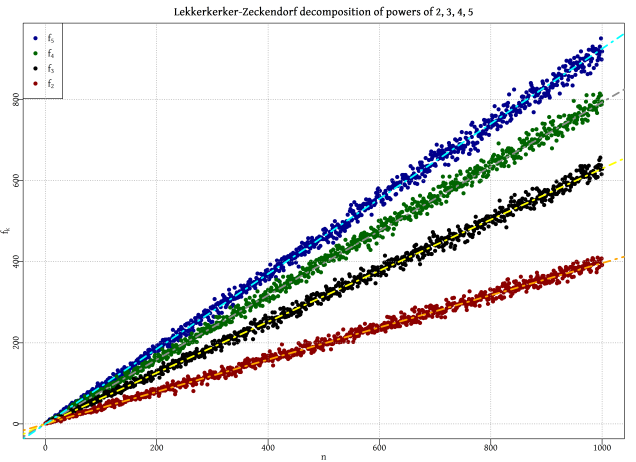

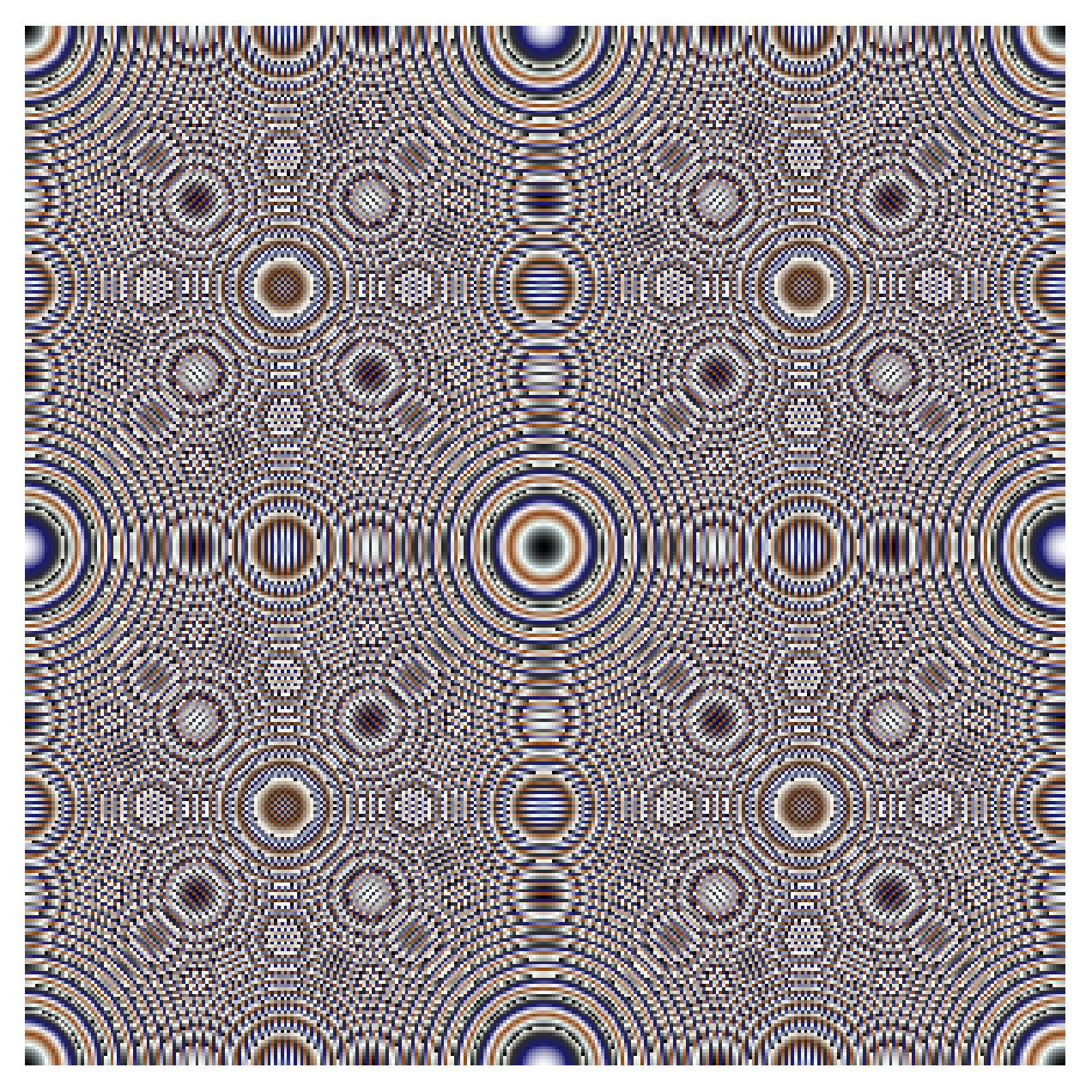

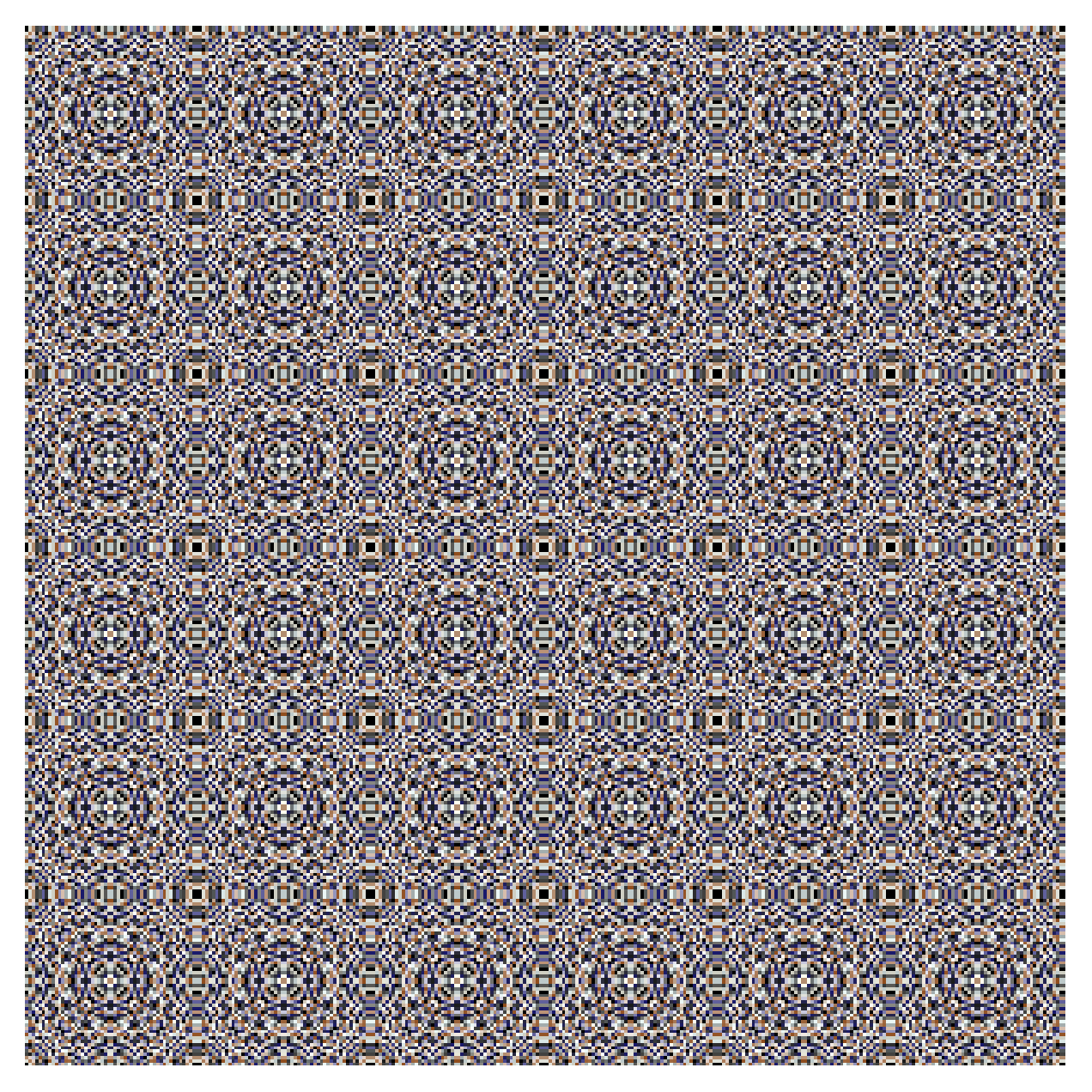

Figure 7. Distribution of the functional iterates of

Figure 7. Distribution of the functional iterates of

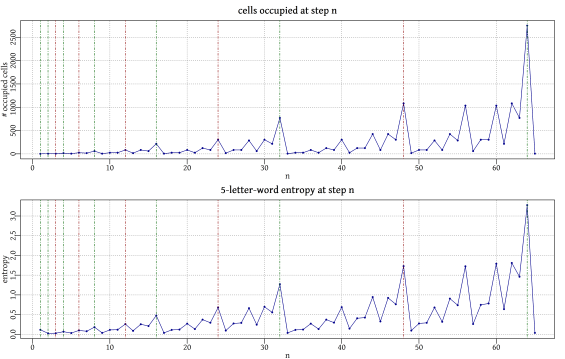

Figure 7. Number of 1 cells and entropy in the evolution of the Ulamian CA on a torus for 1100 steps

Figure 7. Number of 1 cells and entropy in the evolution of the Ulamian CA on a torus for 1100 steps

Figure 5

Figure 5

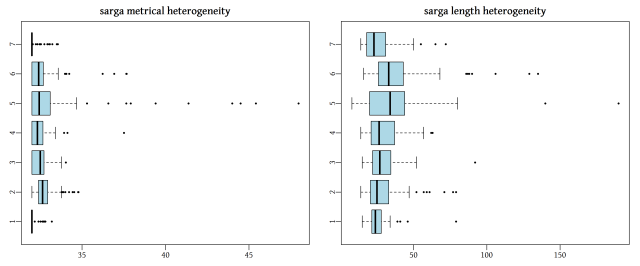

Figure 9. Someśvara’s turagapada.

Figure 9. Someśvara’s turagapada.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 5. A comparable Chingizid era stone from the 1200s of CE housed at the Mongolian National Museum of History.

Figure 5. A comparable Chingizid era stone from the 1200s of CE housed at the Mongolian National Museum of History.

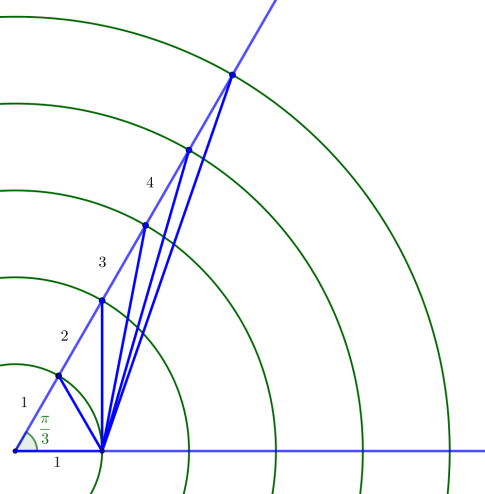

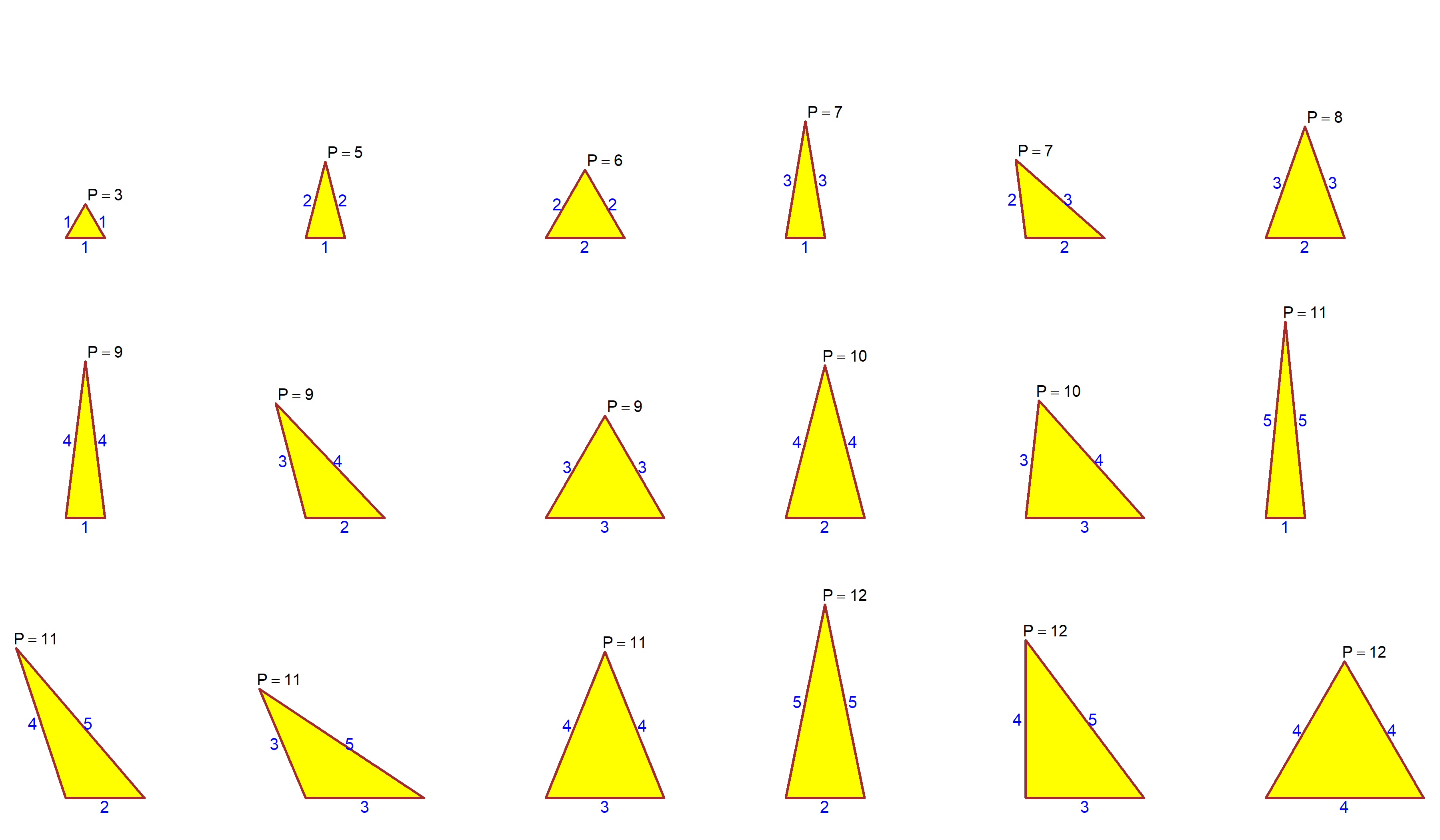

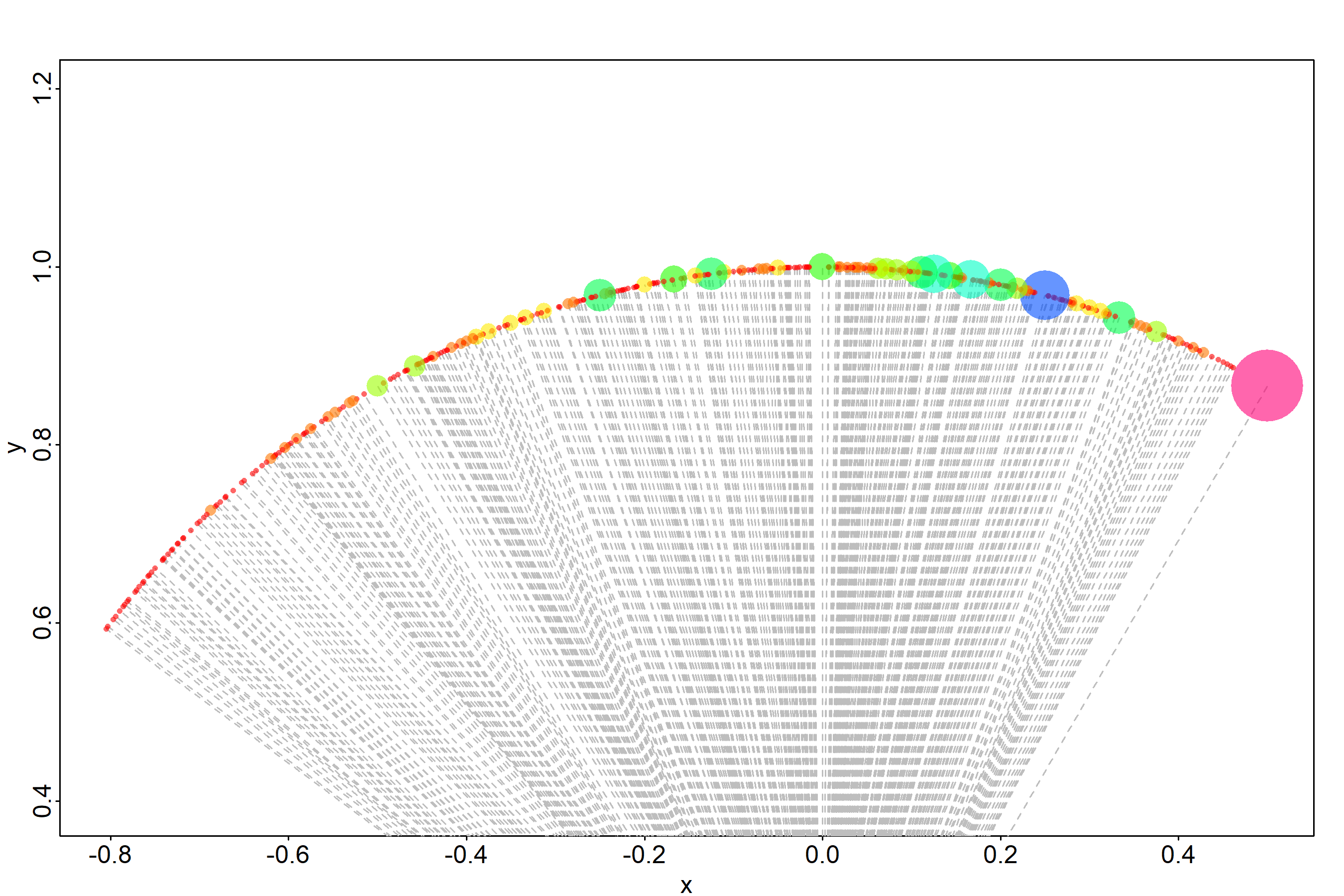

Figure 3. The plots of the largest angles for integer triangles with

Figure 3. The plots of the largest angles for integer triangles with

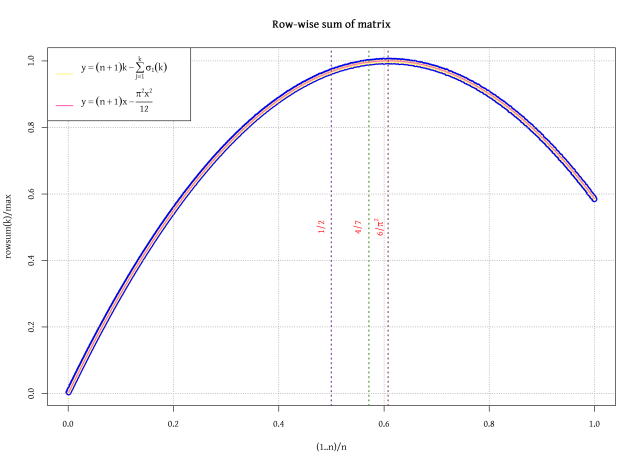

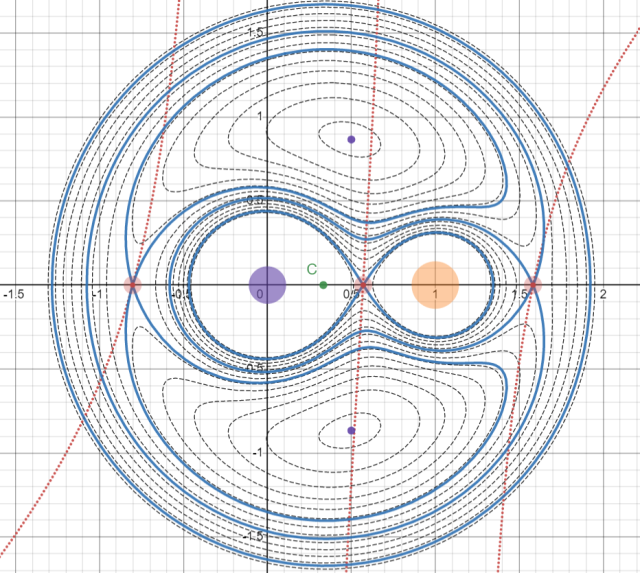

Figure 1:

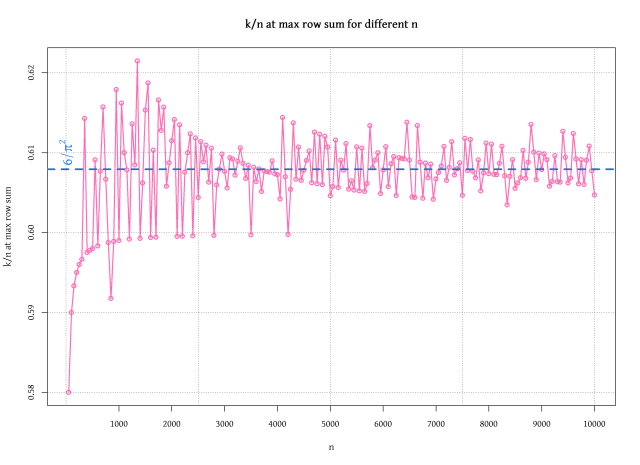

Figure 1:  Figure 2:

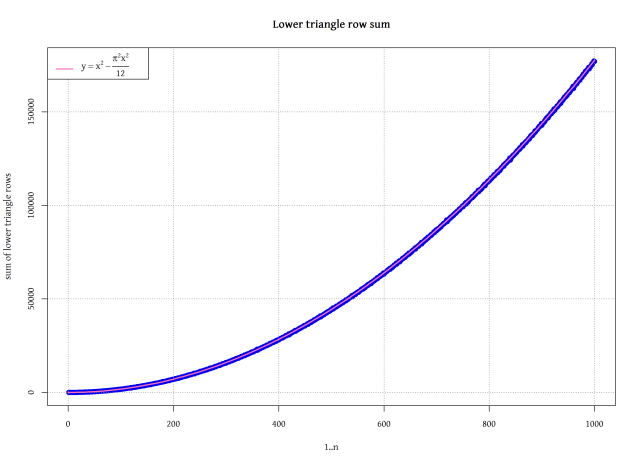

Figure 2:  Figure 3:

Figure 3:  Figure 4:

Figure 4:  Figure 5:

Figure 5:  Figure 6:

Figure 6:  Figure 7:

Figure 7:

Figure 6

Figure 6

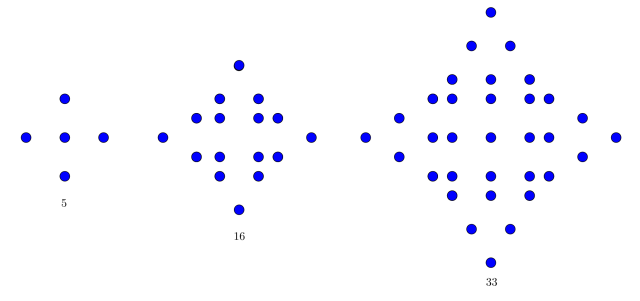

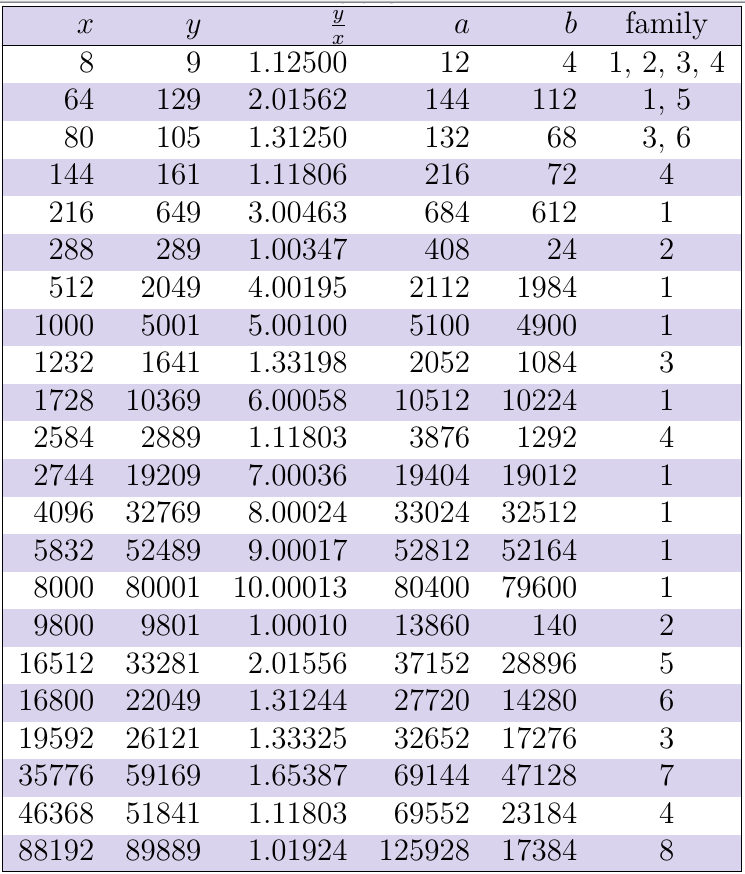

Figure 1. Sum and difference of squares amounting to near squares.

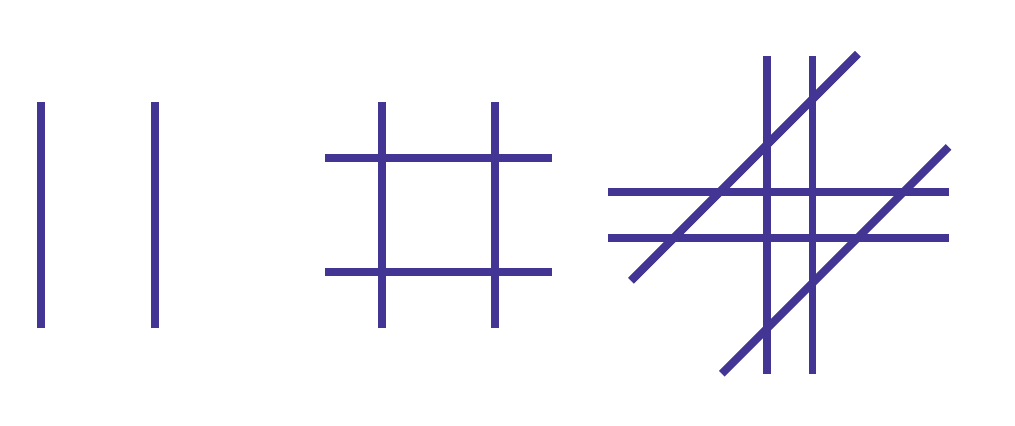

Figure 1. Sum and difference of squares amounting to near squares. Figure 2. Division of plane into regions by parallel lines: 3, 9, 19… regions by 1, 2, 3 pairs of parallel lines.

Figure 2. Division of plane into regions by parallel lines: 3, 9, 19… regions by 1, 2, 3 pairs of parallel lines.

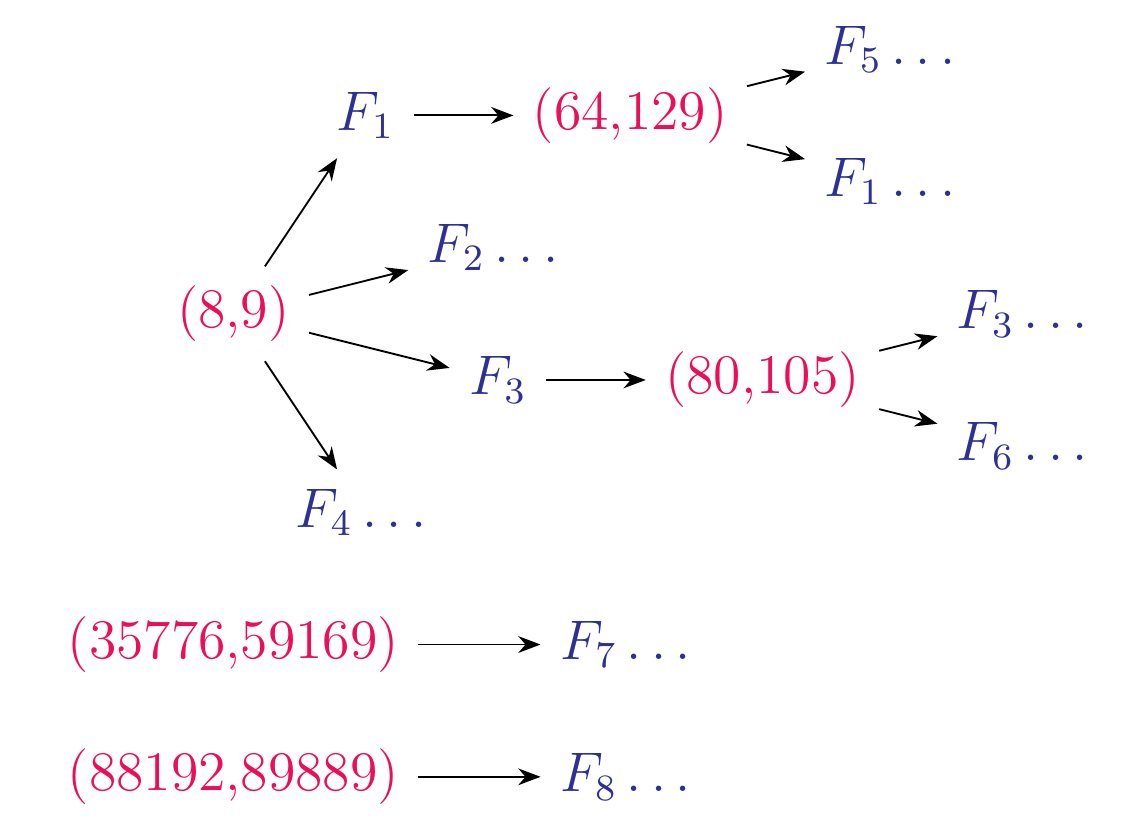

Figure 4. The relationship between families.

Figure 4. The relationship between families.